Though we have known about the harmful effects of excess greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for decades, it has become undeniable that time is running out to avert the worst impacts of climate change – this is the decade in which we must act decisively and ambitiously. Governments worldwide have a critical role to play in mitigating climate change through policy that incentivizes and speeds a transition to cleaner energy, transportation, and food systems. However, it is also imperative that individuals take action to reduce their carbon footprint. Nowhere is this more important than in high-income, high-carbon emission countries like the US, Canada, and Australia where, each year, a single person emits more than three times the global average emissions.i

While individual behavior change alone will not stop climate change, such actions are an essential part of an overall mitigation strategy. They have the potential to be faster and more widespread than policy or technical innovations and can address critical changes like eating habits that are often avoided by governments.ii

A recent book, Under the Sky We Make, by climate scientist Dr. Kim Nicholas, makes the case for individual action based on research she and Dr. Seth Wynes did in 2017. In that study, they identified the most effective actions residents of high income, high emissions countries can take to cut emissions fast: live car free, avoid one transatlantic flight, and eat a plant-based diet. Not only do these three actions each reduce an individual’s GHG emissions by at least 5% – no small feat – they also have the potential to contribute to systemic change in their sector (e.g. fewer cars means lower need for highways).iii

Traditionally, the way policymakers and advocates have tried to encourage uptake of such behaviors has been through interventions focused on the connection between an individual’s attitude about climate change and expected outcomes of a behavior. iv To sway an individual toward pro-climate actions, campaigns generally provide information, such as how much money you could save turning off a light or how many species may go extinct, to try to change beliefs, attitudes, and values about climate change. However, research on the effectiveness of these conventional approaches for motivating uptake of climate friendly behaviors has been critical of the link between simply increasing knowledge or changing attitudes and behavior change.v

Sometimes called “the green gap,” people with pro-environmental attitudes still may not act in a climate-friendly way, yet there has been no “fundamentally different or significantly more effective approach introduced in the last five years.”vi One newer tactic for behavior change interventions recommends a greater focus on the setting in which humans make decisions. In a 2019 meta-analysis of behavior change interventions for climate change, it was found that interventions of this nature, which included social comparison and choice architecture, were among the most effective of those studied.vii

Segmentation, used extensively and effectively in marketing consumer products, offers a more explicitly behavior-focused climate mitigation strategy by tailoring a message or intervention to an audience most likely to take up the behavior. A well-known example of using segmentation for climate change is the “Six Americas” work by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, which identifies six segments in the U.S. based on their beliefs, concerns, and motivations around climate change.viii While this may be an effective segmentation for communications, using it for behavior change still relies on the previously described weak link between attitudes and behaviors. Additionally, though segmentation has driven success in such behavior change efforts as smoking cessation and philanthropic giving, it is a method often “dominated by the individual context, with little consideration for social and material contexts.”ix

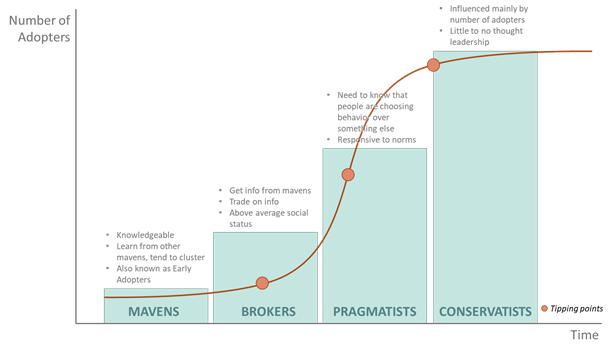

To integrate the effectiveness of segmentation as a targeting tool with the need for behavior change interventions that leverage social influences and norms (i.e. social comparison), we can use what’s known as the social epidemic curve, tipping point, or diffusion of innovation theories. Each of these theories are related to the curve shown belowx, which posits that ideas or behaviors spread virally through society by the social relationships between different groups.

As each successive group adopts an idea or behavior, the behavior becomes increasingly widespread. Capitalizing on this chain link effect, however, requires deliberate and context-driven segmentation. Identifying the right profile of a Maven, for example, will be key to starting the process of changing norms and expectations of personal responsibility around climate change through a “viral” social process. Strategic, research-driven segmentation gives us the tools to look beyond the obvious profile and find the most effective social drivers of behavior change – i.e. for encouraging a plant-based diet, those key segments may not look like a Greenpeace spokesperson but instead could be religious leaders or football players.

We are strongly influenced by those we aspire to be, those we trust, and those we respect. While we still need policy and systems change to fully mitigate climate change’s harmful effects, those of us living in high emission, high income countries have a unique role to play through our individual actions. Leveraging tools that draw on our social nature, like the social epidemic curve, offers an opportunity to magnify the impact of behavior change that mitigates climate change’s worst effects.

________________________________________________________________________

[i] Eggleston, S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., & Tanabe, K. (Eds.). (2006). 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories (Vol. 5). Hayama, Japan: Institute for Global Environmental Strategies.

[ii] Wynes, S. and Nicholas, K.A. Changing behavior to help meet long-term climate targets: The necessity of behavior change to meet climate targets. https://www.wri.org/climate/expert-perspective/changing-behavior-help-meet-long-term-climate-targets.

Williamson, K., Satre-Meloy, A., Velasco, K., & Green, K., 2018. Climate Change Needs Behavior Change: Making the Case For Behavioral Solutions to Reduce Global Warming. Arlington, VA: Rare

[iii] Wynes, S. and Nicholas, K.A. The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environ. Res. Lett. 12 074024 (2017).

iv] Williamson, K., Satre-Meloy, A., Velasco, K., & Green, K., 2018. Climate Change Needs Behavior Change: Making the Case For Behavioral Solutions to Reduce Global Warming. Arlington, VA: Rare

[v] Nisa, C.F., Bélanger, J.J., Schumpe, B.M. et al. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nat Commun 10, 4545 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12457-2

[vi] Black, I. and Eiseman, D. Climate change behaviors – Segmentation study. ClimateXChange, Scotland’s Centre of Expertise on Climate Change. (2019). https://www.climatexchange.org.uk/media/3664/climate-change-behaviours-segmentation-study.pdf

[vii] Nisa, C.F., Bélanger, J.J., Schumpe, B.M. et al. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nat Commun 10, 4545 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12457-2

[viii] Global Warming’s Six Americas. (2021, May 7). Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/.

[ix] USAID. Integrating Social and Behavior Change in Climate Change Adaptation: An Introductory Guide. (2019). https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2019_USAID_ATLAS_SBC%20Guide.pdf.

[x] Adapted from lecture by Brian Uzzi at Northwestern University, 19 September 2018.