Baby bonds are government-established savings accounts set up for children at the time of their birth. The government invests a set amount of capital, often in the $2,000 – $5,000 range (sometimes supplemented with annual contributions) and allows this initial investment to compound until the child reaches the age of 18.

Once the child turns 18, they can use the funds for eligible wealth-building purposes (such as continued education, homeownership, or establishing a business), provided they meet certain basic requirements. Baby bonds target support to children from low-wealth households by using income or other wealth-proxies (e.g., Medicaid) as eligibility criteria for account establishment or as a determining factor in the size of government contributions.

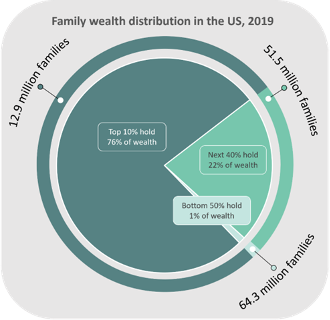

In the US, wealth is acutely concentrated among a small subset of households (many of whom have benefitted from inter-generational wealth transfers), while many others struggle to get by. In 2019, the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) found that the wealthiest decile holds over three quarters of total household wealth, while the bottom half of the distribution holds just one percent of the wealth (see Figure 1). Not only do families at the bottom of the distribution hold little wealth, but over 13 million actually have negative wealth (i.e., debts exceed assets).[i]

Confronting the Racial Wealth Divide

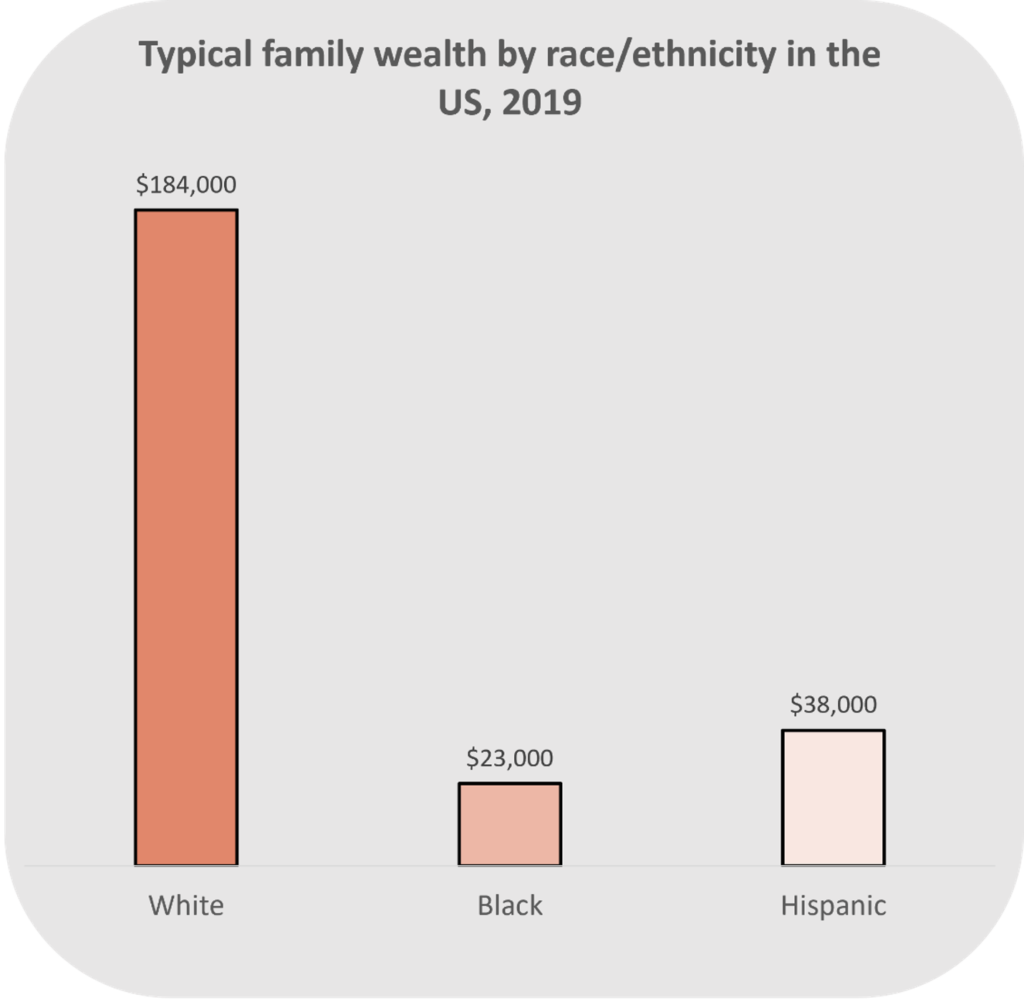

In addition to wealth inequality, a persisting racial and ethnic wealth divide characterizes wealth distribution. For example, in the US, the median Black family ($23K) held just 13% of the wealth compared to their White peers ($184K), and the typical Hispanic family ($38K) held around 20% (see Figure 2). While not all races and ethnicities are represented in wealth data sources (e.g., SCF), income poverty and other wealth-related metrics show that Native Americans and many communities within the Asian American and Pacific Islander category are also excluded from wealth.[ii]

Baby Bonds Legislation

The racial and ethnic wealth divide is primarily the result of historic and continuing systemic inequities that affect people of color in the United States (e.g., land theft from indigenous tribes, enslavement of Black people, the G.I. Bill, redlining and housing discrimination, etc.). Baby bonds policies could, using a race-neutral approach, begin to correct some of those inequities that underlie the racial and ethnic wealth divide. Gaining access to one’s baby bond account at age 18 could mimic the advantage of intergenerational wealth transfers that wealthier, typically, white) families, and propagate inequalities through generations. By providing young adults with money specifically for wealth-building purposes, baby bonds can help interrupt the status quo and create opportunities for BIPOC*, lower-income, and other disadvantaged communities to seed wealth for themselves and for future generations.

While economists William Darity Jr. and Darrick Hamilton first proposed baby bonds as a way to close the racial wealth divide in 2010,[iii] it wasn’t until eight years later that the first federal legislation was put forward. Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) proposed the American Opportunity Accounts Act, in which every child’s account would be seeded with a $1,000 deposit upon birth, with tiered annual contributions dependent on family income.[iv] As a result, children from the poorest households would have an estimated balance of $46,000 at their 18th birthday, while peers from the wealthiest households would receive under $2,000.

While Booker’s initial proposal did not advance, he, along with Massachusetts Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA), reintroduced the American Opportunity Accounts Act in 2021 with broader support from co-sponsors.[iv]

In addition to federal legislation, several states have proposed—and even passed—local baby bonds policies.

- Connecticut: In July 2021, Connecticut paved the way by enacting the CT Baby Bonds legislature.[vii] CT Baby Bonds will automatically enroll babies born under HUSKY (the state’s Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program) starting in July of 2023. Upon birth, the state will deposit as much as $3,200 into the CT Baby Bonds Trust, to be invested and managed by the Office of the Treasurer. In order to access funds, beneficiaries must be 18-30 years old, complete a financial literacy course, and currently reside in the state. When those conditions are met, young adults can then make a claim to request funds for one of the designated eligible purposes: higher education, homeownership in the state, investment in a business in the state, or retirement savings. See the full legislation here (Sec. 104-110).

- District of Columbia: The DC Council approved the Child Wealth Building Act by a unanimous vote in October 2021.[viii] The Child Trust Fund Program established by the act will automatically enroll babies whose birth is covered by DC Medicaid and that are born to households with income 300% or less of the federal poverty line and enrolled in DC Medicaid.[ix] Accounts for eligible babies will be seeded with an initial $500 deposit and grown with annual contributions of up to $1,000, dependent on family income. If the previously eligible child’s household becomes ineligible at any point before their 18th birthday, annual contributions will cease but the existing balance will still be available for later distribution. At 18 years of age, beneficiaries of the Child Trust Fund Program residing in the district can receive distributions to be used for the following purposes: education, ownership or investment in a DC business, ownership of a DC property, or retirement investment. See the full legislation here.

Beyond Connecticut and DC, baby bonds legislation has been discussed in California[1], Delaware[2], Iowa[3], Louisiana[4], Maryland[5], Massachusetts[6], Nevada[7], New Jersey[8], New York[9], Washington[10], and Wisconsin[11].

Washington Future Fund: Camber’s Work in Baby Bonds Policy

In 2022, the Washington Office of the State Treasurer (OST) contracted Camber Collective, with partner Prosperity Now, to conduct a wealth inequity study. The Washington Future Fund Study Committee—made up of elected officials, community representatives with lived experience, and members of economic empowerment organizations—would then leverage the wealth inequity study, along with their other work, to make recommendations to the state legislature regarding baby bonds policy in Washington. To present a comprehensive understanding of wealth inequities in Washington, we utilized quantitative analysis of household- and individual-level data, qualitative analysis of interviews with low- and middle-income Washington residents, and secondary research of exiting literature throughout the study.

Our research identified racial/ethnic and geographic wealth divides in the state, informed by stories from individuals experiencing challenges in building wealth. The final report (excerpts included in OST’s report to legislature contextualizes wealth disparities with exploration of why wealth matters, summary of how inequities are created and perpetuated, and discussion of the implications of wealth inequities on households and the state economy. The insights surfaced through the research study, complemented by Prosperity Now’s expertise in baby bond policy, resulted in a series of evidence-driven policy recommendations for the state legislature’s consideration in the 2023 session. This work, along with the research study report, was highlighted recently in the Seattle Times.

[i] Can ‘Baby Bonds’ Eliminate the Racial Wealth Gap in Putative Post-Racial America? – Darrick Hamilton, William Darity, 2010 (sagepub.com

[ii] An exclusive look at Cory Booker’s plan to fight wealth inequality: give poor kids money – Vox

[iii] Booker reintroduces ‘baby bonds’ bill to give all newborns a $1K savings account – POLITICO

[iv][Can ‘Baby Bonds’ Eliminate the Racial Wealth Gap in Putative Post-Racial America? – Darrick Hamilton, William Darity, 2010 (sagepub.com)

[v] An exclusive look at Cory Booker’s plan to fight wealth inequality: give poor kids money – Vox

[vi] Booker reintroduces ‘baby bonds’ bill to give all newborns a $1K savings account – POLITICO

[ix] DC Council unanimously ‘baby bonds’ bill – WTOP News [1] Chapter 6D. Building Child Wealth. | D.C. Law Library (dccouncil.gov)

[1] California approved budget for the Hope, Opportunity, Perseverance, and Empowerment for Children Trust Account Fund, which will target low-income children who lost a primary caregiver to COVID-19 and foster children

[2] Legislation introduced in 2022

[3] Legislation introduced in 2021; note that this policy would have created opt-in accounts for all babies in the state, regardless of wealth

[4] Resolution passed in 2022 to commission study on baby bonds to be delivered for 2023 session

[5] Proposed by governor-elect

[6] Task Force conducted study in 2022

[7] Treasurer requested legislature to draft a bill for baby bonds

[8] Legislation re-introduced in 2022; note that, in 2020, Governor Murphy called on lawmakers to implement baby bonds, though budget was finalized without the necessary allocation

[9] Legislation introduced in 2021 (multiple versions)

[10] Legislation introduced in 2022; study committee established to provide recommendations for 2023 session

[11] Legislation introduced in 2021

Rebecca Drachman is an analyst at Camber Collective. Her work at Camber thus far has included several projects in the Shared Prosperity sector, including with a direct services nonprofit, large family foundation, and, most recently, state government. Before coming to Camber, Rebecca studied Psychology and Neuroscience and conducted neuro-imaging research at Yale University. She is passionate about leveraging quantitative and qualitative research approaches to solve pressing problems and elevate marginalized voices.

Marc Allen is a Director at Camber Collective and heads the firm’s Shared Prosperity portfolio. Drawing on his toolkit as a strategist and former policy attorney, Marc leads teams working to strengthen and reimagine our economic and democratic systems. His experience spans strategy and investment design, human-centered research/insights, and coalition-building services for philanthropies, government agencies, multilateral institutions, nonprofits, and socially-invested corporations. More broadly, Marc guides the effectiveness of executive teams in mission-driven organizations, helping to advance their theories of impact, program design, business models, and cultures of belonging.