… Between the Redetermination Process, Expanded Maternal Coverage, and the Ongoing Struggle for Health Equity

Introduction

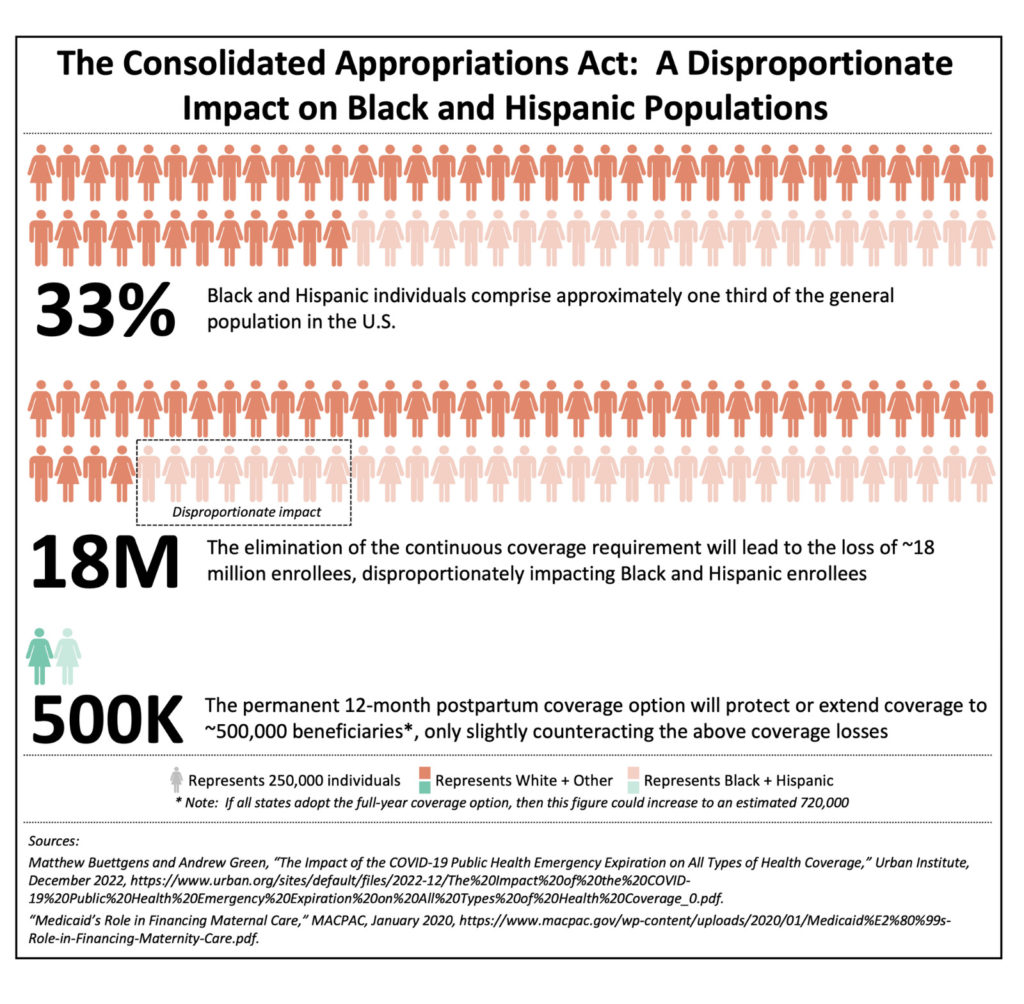

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, passed in December 2022, illustrates how any change to the American social safety net requires sub-optimal compromises and trade-offs. This give and take is particularly present in today’s partisan political environment. Case in point: the $1.7 trillion federal omnibus spending bill introduces Medicaid provisions that will simultaneously reduce insurance coverage for certain enrollee subgroups while expanding it for others—effectively creating a coverage tug of war among our most vulnerable populations. While this legislation can be seen as a victory for maternal health coverage (albeit a somewhat limited one), in aggregate it will likely reduce access to care for those who need it most. The maternal health provisions will undoubtedly help improve both gender and racial health equity in maternal and newborn care; however, the Medicaid redetermination process will have a disproportionately negative impact on current Black and/or Hispanic* enrollees (see Figure 1).

Evolution of Medicaid Coverage in the Wake of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency

To anticipate and address the nation’s healthcare needs during the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE), the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) was signed into law in March 2020. Notably, the FFCRA provided increased federal Medicaid funds to states with the stipulation that they abide by specific requirements, including prohibitions on involuntary disenrollments and decreased income eligibility levels. Over the past three years, the Act’s continuous coverage provision has played an effective and impactful role in mitigating both Medicaid “churn” (the temporary loss of coverage in which enrollees disenroll and then re-enroll within a short period of time) as well as the outright loss of coverage that often occurs due to changes in employment status and/or income.[i]

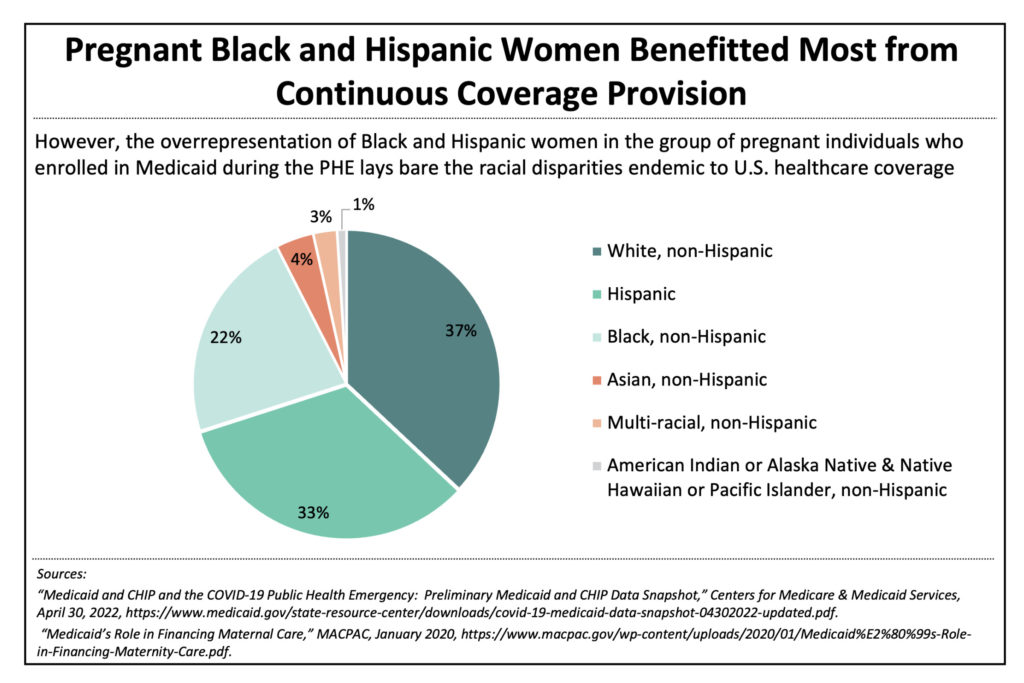

As a result, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) estimates that Medicaid ranks swelled by 20.5 million enrollees between February 2020 and October 2022, a massive 32% increase. The net impact of the FFCRA is 91 million Americans, including 41 million children, being covered by Medicaid and CHIP programs—a record.[ii] The primary driver of Medicaid enrollment growth was not the addition of new program participants but rather the retention of existing enrollees.[iii] Notably, the pregnant individuals eligibility group experienced the greatest increase in enrollment during the pandemic, adding more than 650,000 expectant-mother beneficiaries to the Medicaid program, a 62% increase over pre-pandemic numbers. Not only does the enrollment increase for this subgroup point to a significant gap in maternal coverage under pre-pandemic policies, it also highlights the marked health disparities between racial groups in the U.S.[iv]

Despite making up about one third of the general U.S. population, pregnant Black and Hispanic women** comprised approximately 55% of the increase in expectant-mother Medicaid beneficiaries due to the continuous coverage provision (see Figure 2). Without the protections offered by this type of provision, pregnant Black and Hispanic individuals struggle more than other racial and ethnic groups to secure and maintain access to coverage, putting both mother and baby at risk.

After three years of steady and stable Medicaid expansion, the 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act is poised to eliminate a significant portion of these coverage gains. The legislation eliminates the continuous coverage requirement as of March 31, 2023, allowing states to once again begin the process of Medicaid eligibility redeterminations and disenrollments. The federal government implemented guardrails to ease the Medicaid redetermination process such as a gradual ramp down of the enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) match implemented during the public health emergency and data reporting requirements for the states. Unfortunately, such provisos will not prevent significant loss of coverage for many people because most states simply do not have the budget surplus necessary to sustain higher coverage without the injection of enhanced federal assistance.

The Impact of Coverage Redetermination on Racial Health Equity

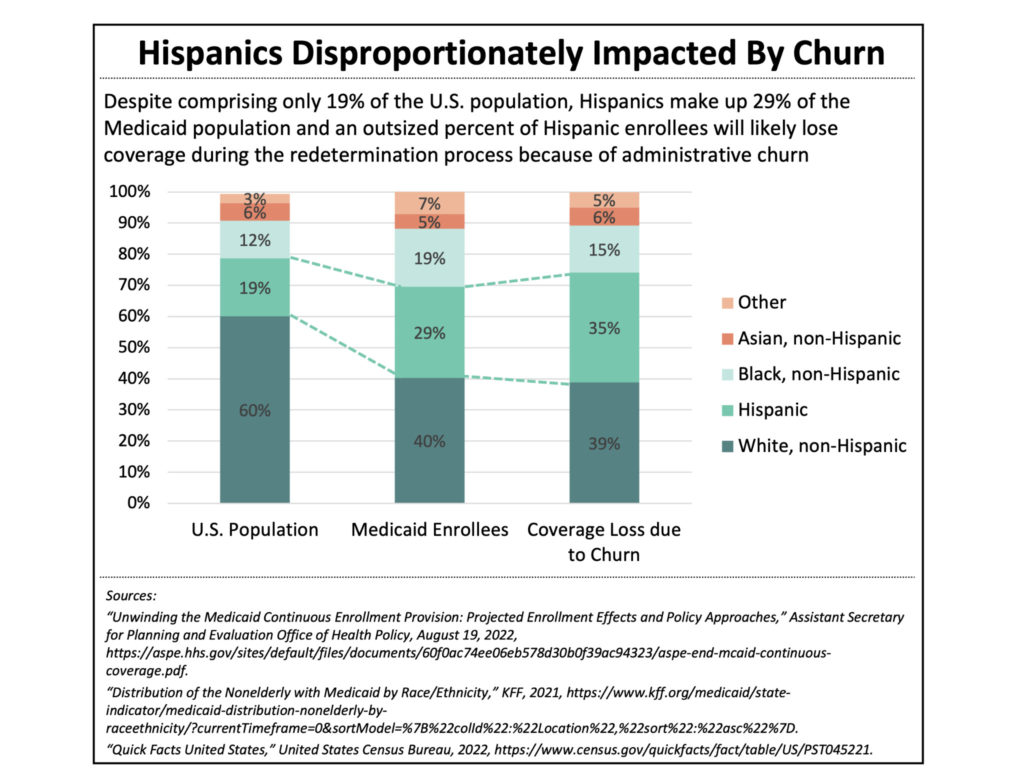

The Urban Institute estimates that 18 million people will lose Medicaid coverage between April 2023 and May 2024, with approximately 4 million becoming uninsured as a result.[v] The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) projected that approximately 45% of those people likely to lose Medicaid, either due to the outright loss of eligibility or administrative churn, are Black or Hispanic. The disparity is striking when one considers that these groups combined comprise only 33% of the American population.[vi]

According to HHS estimates, approximately 7 million eligible people will lose Medicaid coverage solely due to administrative challenges resulting from the redetermination process. These administrative roadblocks requiring beneficiaries to “prove” their eligibility include lengthy wait times, unreasonable deadlines, burdensome and missing paperwork, lack of knowledge about the redetermination process, and incorrect contact information. The structural racism embedded in American social systems further exacerbates the difficulties faced by People of Color, who are more likely to experience housing and employment volatility. The compounded issues make it difficult for state agencies to contact eligible individuals and verify administrative details such as income level and current address. For this reason, Hispanic enrollees are more likely to lose coverage due to administrative issues than white Medicaid enrollees (see Figure 3).[vii]

The Impact of the Recent Federal Legislation on Maternal Health

Prior to the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP), federal statute mandated that states provide pregnancy-related Medicaid care for only 60 days postpartum with a minimum income threshold of 138% of the federal poverty line (FPL). While some individuals would qualify for Medicaid coverage via other means after this 60-day window closed, an estimated 45% of new mothers would lose coverage under this stipulation.[viii] Effective April 2022, the ARP gave states the option to extend postpartum care and receive matching federal funds for 12 months of post-birth coverage through the use of state plan amendments. The stipulation that this option would expire in 2027 led some states to demur from expanding coverage that would need to be rolled back in the near future. Given the unacceptable U.S. maternal mortality rate—The Commonwealth Fund estimated that the U.S. recorded 23.8 maternal deaths for every 100,000 births in 2022, a maternal mortality rate that is more than three times that of France, the country with the second-highest rate among developed nations [ix]—a concerted effort was undertaken to advance maternal health. A stipulation in the December, 2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act provided a fortuitous outcome as it eliminated the 2027 expiration date, thereby establishing permanency for the 12-month postpartum coverage option.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the postpartum period as beginning at childbirth and lasting around six weeks, encompassing the time during which the mother‘s body begins transitioning to a non-pregnant state. While an estimated 35% of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. occur between one and 42 days postpartum, approximately 30% occur between 43 and 365 days postpartum. [x] This statistic clearly indicates that after-birth care must extend beyond the generally accepted six-week postpartum period. Loss of insurance coverage and lack of access to care are driving factors of many of these deaths, including those that occur months after giving birth. According to the CDC, between 60% and 80% of all pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Thus, the pre-pandemic federal policy that mandated only 60 days of postpartum coverage created a potentially life-threatening gap in care, one that inordinately impacted nonwhite individuals. As an example, Medicaid covers approximately 40% of births nationwide—2 million mother-baby pairs—but that number increases to nearly 70% for Black individuals.[xi] Furthermore, maternal mortality rates are three times higher for Black women than white women.[xii]

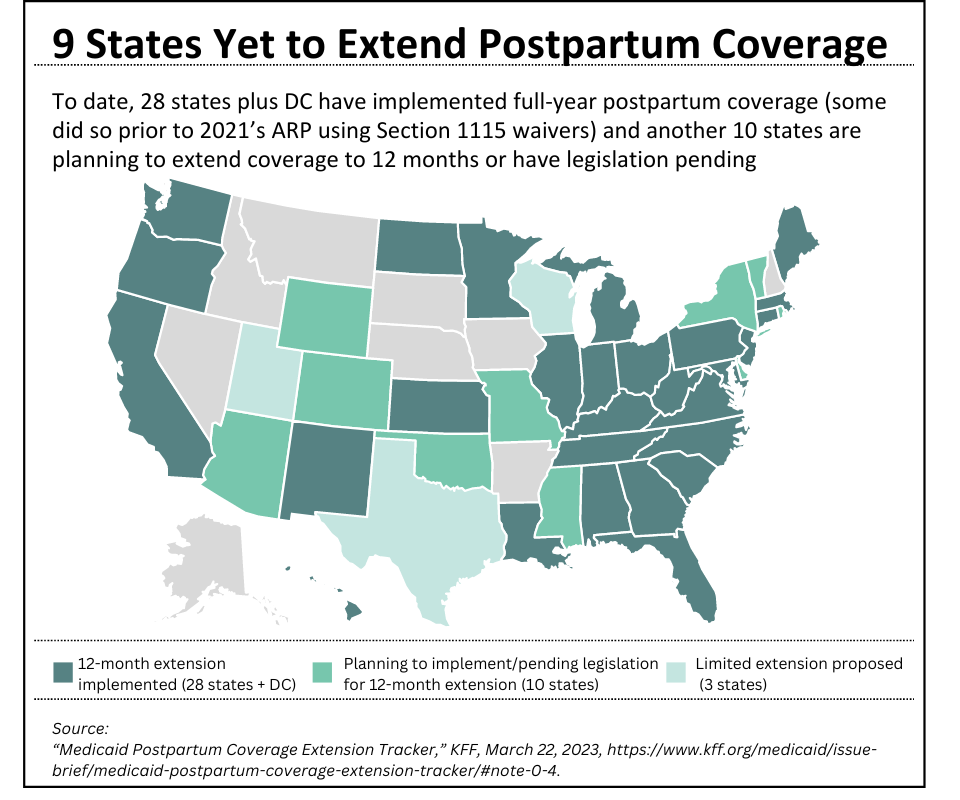

While the coverage extension option is undoubtedly a step in the right direction for maternal health, the fact that it remains an option for states, rather than a mandatory requirement, certainly blunts the policy’s impact. Despite this deficiency, a majority of states currently support expanded coverage. As of March 2023, 28 states plus the District of Columbia have elected to adopt 12 months of postpartum coverage; it is expected that additional states will follow suit this year (see Figure 4).[xiii] It is estimated that this policy change has provided approximately 500,000 individuals with extended postpartum coverage and, if all states adopt the measure, an estimated 720,000 people would be eligible for a full year of postpartum care.[xiv]

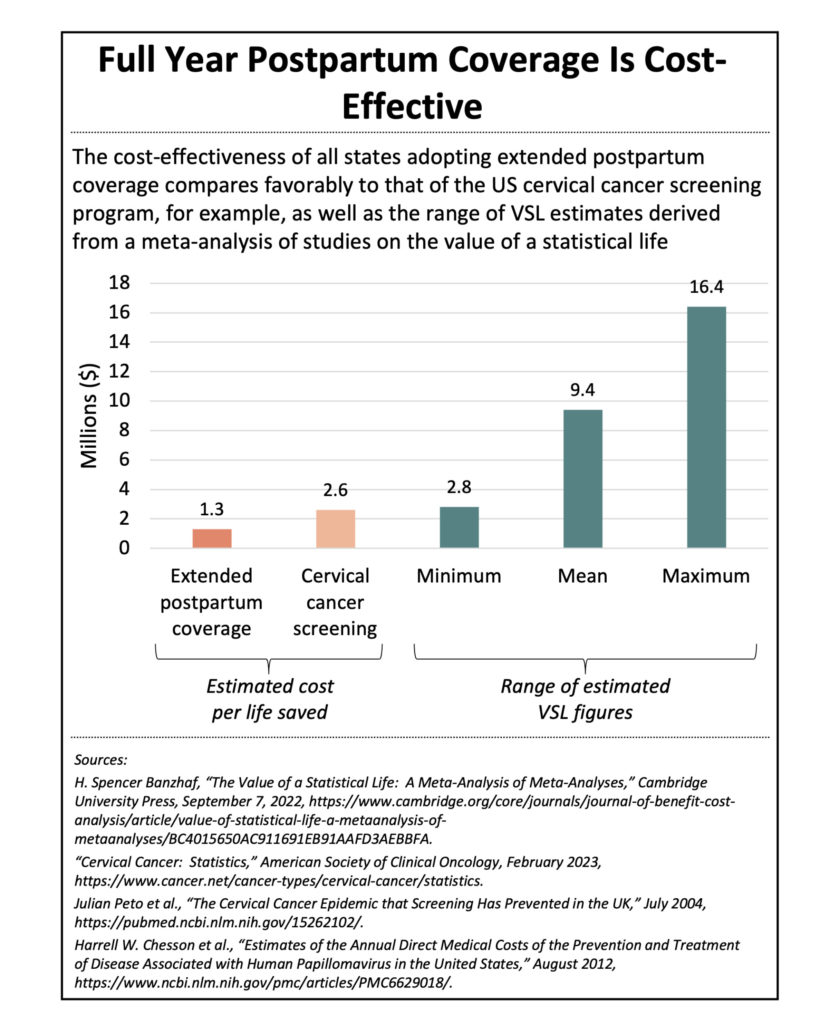

According to Congressional Budget Office estimates, it would cost the federal government $1.2 billion over 10 years if all 50 states plus the District of Columbia implemented the extended postpartum coverage provision.[xv] Assuming that the U.S. live birth rate increases 1% per annum over the next decade, while the maternal mortality rate remains constant, many lives would be saved. Indeed, our calculations project that, if all states extended postpartum coverage from 60 days to a full year, approximately 960 maternal deaths would be prevented.

Even beyond the moral imperative of valuing the lives of each expectant mother in America, the economics of savings lives is obvious. Expanding upon the above scenario, the estimated cost per life saved would be $1.3 million, well below the mean value of a statistical life (the estimate of the willingness to pay for small reductions in mortality) of $9.4 million in today’s dollars (see Figure 5).[xvi] [xvii] The implementation of full-year postpartum coverage across all states is clearly a cost-effective policy in addition to an ethical one.

It is worth noting that this analysis likely underestimates the cost per life saved by extending postpartum coverage, because the calculation assumes a constant maternal mortality rate. The fact is however, that extending coverage to a full year will undoubtedly decrease this rate even further. Additionally, the cost per life estimate of extended postpartum coverage likely fails to fully reflect the overall positive impact and effectiveness of this policy since it does not account for the holistic impact on mother and child health.

Extended postpartum coverage is an issue that cuts across partisan boundaries—at least to some extent. Of the 24 states that have banned or are expected to ban abortion since the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June 2022, half have elected to provide a full year of Medicaid coverage post-birth.[xviii] Notably, seven of the 11 states that have not expanded Medicaid in the wake of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), such as Georgia, Florida, and Tennessee, have implemented full year postpartum coverage. While the expanded postpartum coverage is undeniably helpful in improving maternal health outcomes, for many people, it simply postpones the inevitable loss of coverage, especially in the non-Medicaid expansion states where income limits for non-pregnant adults are typically well below 138% FPL.[xix] [xx] On the other hand, a number of Medicaid-expansion states such as Arkansas have been slow to extend postpartum coverage to a full year. This state consistently ranks among the worst in the nation when it comes to maternal mortality with 30.2 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. This rate greatly exceeds the national average of 23.8.[xxi] When racial disparities are layered on top of such dismal statistics, the outcomes are even more stark. In Arkansas, Black mothers are more than twice as likely to experience a pregnancy-related death than white mothers.[xxii]

It is likely that not all states will elect to provide 12 months of continuous postpartum care, putting numerous mothers at risk, with nonwhite mothers bearing more of that risk, especially in those states that have implemented abortion bans in the post-Roe era. In December 2021, the University of Colorado quantified the uptick in pregnancy-related deaths that would occur due to the heightened mortality risk of continuing a pregnancy as opposed to having a legal abortion—a 21% increase across all women, but a 33% rise for Black women.[xxiii] While this study, published in advance of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, assumes a national ban on abortions and is not specifically focused on the postpartum period, the findings are illustrative of the U.S.’ inequitable maternal health policies.

Looking Forward

Since 2020, the federal government has passed a patchwork of legislation, much of which contained embedded critical health policy shifts, even though healthcare was rarely the principal focus of such legislation. Not surprisingly, this approach creates outcomes that lack coherence and consistency in terms of their effect on the Medicaid safety net. This access and equity tug of war is emblematic of the often-paradoxical impacts of Medicaid, the “single most important publicly funded health program for low-income and underserved people,” yet one that suffers from “racism baked into the system” because it was established as an optional program for states borne out of the country’s pre-existing welfare infrastructure.[xxiv]

To amplify the positive effects of the Medicaid policy changes taking effect this year, key stakeholders such as state agencies, advocacy groups, philanthropic organizations, Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs), communications specialists, and health technology companies should pursue targeted tactical activities, including the following:

1. Leverage Data and Community-Based Outreach

Those states that have elected to extend postpartum coverage to a full year should launch targeted outreach campaigns to ensure that everyone eligible takes full advantage of this expanded access to care, especially pregnant Black and Hispanic women. These campaigns should be multi-faceted and data-driven, bringing together key stakeholders in support of shared goals. Furthermore, this outreach should leverage community-based approaches that revolve around specific needs and circumstances as well as tap into trusted relationships. Campaign messaging should be designed strategically, taking into account the particular preferences and attitudes of different communities.

2. Take Steps to Limit Administrative Churn

To mitigate the negative effects of what is sure to be a burdensome redetermination process, states should endeavor to minimize administrative churn as much as possible, especially among Hispanic beneficiaries, leveraging enrollment navigators as well as working with peer social services or support organizations to confirm and share contact information. Additionally, states should seek to both improve the ex parte renewal process, the first step in Medicaid redetermination whereby states can automatically attempt to renew coverage by consulting available data sources to confirm eligibility for certain enrollees, as well as increase the number of successful ex parte renewals. One method is to review the internal documents that define which cases can be renewed ex parte and determine what reasonable changes could be made to the definition and the business rules undergirding the renewal system itself. Additionally, it may be helpful to leverage supplemental data sources such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to increase the percent of cases successfully handled via the ex parte process.[xxv]

3, Engage Partners for Support

State agencies and Medicaid MCOs should consider seeking temporary external assistance to help share the workload and mitigate churn. Philanthropic funders can help bridge the gap here, providing financial support to implement or expand navigator programs and facilitate data sharing. Additionally, healthtech innovators have the opportunity to step in and provide solutions related to data management and systems optimization.

*While “Hispanic” and “Latino” are often used interchangeably, and many readers show a preference for one or the other designation, or perhaps “Latino/a/e/x,” this paper uses “Hispanic” to align with Census and other federal data tracking conventions

** In line with statutes and regulations, Camber uses the term “women” when referencing individuals whose sex assigned at birth was female; however, we recognize that not all people who give birth identify as women.

Kim Langenhahn draws on more than 15 years of consulting, operational, and startup experience in the domestic and international health and nonprofit sectors to help organizations navigate complex issues, operate more effectively, and deliver greater impact. During the course of her career, Kim has helped numerous healthcare organizations tackle a variety of strategic challenges such as scaling Terrapin Pharmacy’s remote medication adherence system, launching a MENA-focused healthcare incubator, devising system-wide strategy for the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health as part of PwC’s consulting practice, and developing a market forecast for a pharmaceutical company alongside her L.E.K. Consulting colleagues. She is also the Cofounder of a small social enterprise that she runs with her family

Kim earned a Master of Business Administration and a Master of Public Policy from the University of Chicago as well as a Master of Science in Quantitative Management and a Bachelor of Arts from Duke University. An avid traveler, reader, bread baker, ice cream churner, and (aspiring) cheese maker, she also enjoys helping her husband tend to their rooftop garden and vermiculture operation. She currently resides in Washington, D.C.