Summary

US inflation has surged over recent years primarily as a result of supply-side challenges coupled with rising profit margins and labor costs. Although levels are now beginning to moderate, many still feel the sting of higher prices. In particular, inflation disproportionately impacts low-income households in light of the ways in which these households typically earn, spend and save. In response, philanthropies should focus part of their financial and non-financial resources on supporting cash transfer programs, consumer protection measures, application of disaggregated inflation insights, and improved financial literacy, thereby filling gaps not fully addressed by federal government at the current time.

State of US inflation

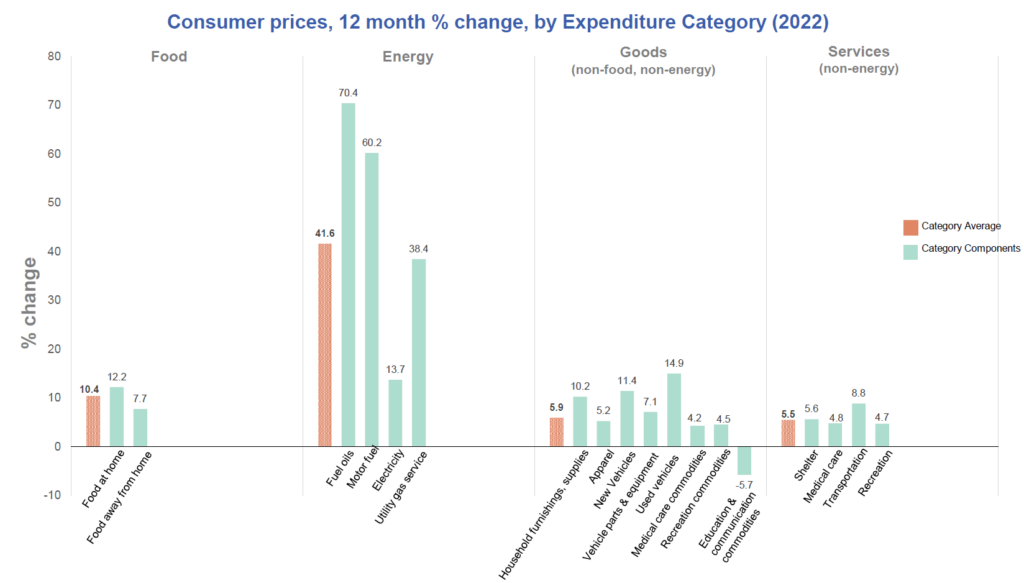

In 2022 inflation reached 9.1%, its highest rate in 40 years. Of the goods and services contributing to that value, groceries, various types of energy, motor parts & equipment, and household furnishings and supplies were among the most notable increases.1

Figure 1, adapted from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Though inflation has moderated to an average annualized rate of ~5% in 2023, this aggregate value masks the fact that the most essential goods and services, such as food 2 and medical care, have remained well above this level. Similarly, while gasoline prices have fallen since peaks seen in 2022, both motor and diesel fuel are currently higher than they were in the four-year period from mid-2017 to mid-2021.3

Significant decreases have primarily been seen in valuable, but not essential, categories such as household appliances, clothing, and even recreational equipment.4

The Unequal Impact of Inflation on US Households

Many people experience inflation as a slight frustration, or as a cause for mild concern. Reactions to price increases are expressed as indignation at higher grocery bills and irritation at the climbing costs of long-used products and services (which are ultimately still consumed)

However, the experience can be entirely different for lower income households, for whom ongoing inflation is imposing profound economic and even socio-emotional distress. For lower-income households, sustained periods of inflation can completely shift quality of life and in some cases, even risk access to basic rights, such as adequate availability of healthy food, consistent supplies of clean water, reliable electricity, and more. Notably, price inflation not only threatens economic security for these households – it also frequently stalls or reverses any prior economic mobility they may have experienced. High inflation rates have been linked to a reduction in the US middle class and a return to poverty for those who recently came out of the lowest income and wealth quintile.

Three factors explain the heavier impacts of inflation on lower-income households. Each of these reasons corresponds to a particular phase in the income lifecycle:

- How you earn: First, lower-income households are more likely to be employed informally in certain sectors, (child care, yard work, cleaning, etc.) relying primarily on wage income or transfer payments, or to occupy roles with diminished bargaining power. This fact is often due to a high supply/replaceability of workers for those roles and/or lack of union representation. Unfortunately, inflation has particularly outpaced growth in wages and transfer payments for these roles, which equally tend not to provide supplemental benefits such as sick leave or retirement contributions.6 In contrast, middle and higher-income households are often employed in sectors that offer salaries and benefits such as commuter stipends or caregiver benefits, leaving them less vulnerable to price shocks in the economy.

- How you spend: Second, lower-income households typically spend a greater percentage of their income on necessities such as food, energy, and housing. Studies have shown that lower-income households in developed countries can spend as much as 50% of their income on food while higher-income households spend 20% on this expense.6 While higher-income households can use tactics such as couponing or purchasing cheaper options to maintain key aspects of their lifestyles, lower income households often already use such money management tactics and therefore, have no further “dollar stretching” to do. As a result, lower income households are often forced to buy goods and services of extremely low quality, or have no choice but too completely forego necessities during times of price inflation. 7

- How you save: Third, lower-income households are more likely to live paycheck-to-paycheck and have less discretionary income. As a result, these households often do not have an emergency fund or extensive savings and are more likely to go into formal debt (i.e. credit card, loans) or informal debt (i.e. borrowing from loved ones) to pay for necessities.8 A lack of discretionary income and savings, as well as diminished access to or trust in financial systems9 reduces many lower income households’ exposure to services and financial planning/investment approaches of potential benefit to them, further distancing them from obtaining the highest value from the money they do earn in the short and long-term.Conversely, middle and higher-income households have greater access to financial markets and often hold investments, resources which have a greater likelihood of shielding them from inflation’s harms.10

Approaches to Addressing Inflation

Given the extreme economic precarity that price inflation can bring to lower-income households, philanthropies may consider mobilizing their resources to complement, or fills gaps in, government approaches emanating from the federal, state, or local levels.

Of the various approaches we have seen philanthropies engage with, four warrant particular consideration for the level of innovation they represent:

- Direct Cash Transfers: In times of rapid economic change, some philanthropies – notably community and place-based foundations – have ventured into the direct cash transfer space, providing rapid cash (on a needs-based scale) for essential goods and services critical for by low-income households. Transfers may be earmarked for specific objectives (such as gas or energy relief, health services, rent assistance, reduced internet service payments, etc), or may be unrestricted. One of the pioneers of this approach was the Greater Washington Community Foundation, which supported 60,000 residents of the Greater Washington DC area with payments totaling $26 million throughout the pandemic, and whose approaches remain highly relevant in this inflationary period.

However, cash transfer programs should be implemented and monitored carefully to ensure that the intended effect is produced. In some instances, cash transfers have been shown to suddenly stimulate consumption, leading to reduced supply and even higher prices. Conversely, others have argued that increased purchasing power leads to product variation and resultingly, price decreases.11 The variable outcome of cash transfer programs are influenced by several characteristics, including scale of implementation (geographic area and/or number of individuals), the monetary amount per transfer, the number and cadence of transfers, and more.12 Making evidence-based design decisions that are tailored to the inflation context increases the likelihood of positive, intended economic effects.13

- Antimonopoly Engagement: While corporate concentration (i.e. monopolies) in key industries constitutes just one of several market contributors to recent inflation, this factor alone is estimated to cost the average American $5k per year in distorted (inflated) prices. In the absence of a competitive market, there is little rein on whether businesses monopolizing the market raise their prices acutely.14 Traditionally, philanthropy has not engaged in ideological questions around the paradigms that govern our economy, including monopolistic practices that have escaped antitrust policy and enforcement since the 1980s. Yet this hesitancy is slowly evolving, led by major funders such as (but not limited to) the Ford Foundation, Omidyar Network, Hewlett Foundation. Now is an opportune moment for philanthropy to make a difference. A leading forum for action has been the Economic Security Project’s Antimonopoly Fund, which has “leaned into what was missing from the movement: grassroots organizing power around anti-monopoly campaigns, academic research that filled critical gaps in our understanding of the problem and potential solutions, and culture- and narrative-shift projects that told and made accessible the stories of how monopolies have impacted individuals and communities.”

- Improved Application of Disaggregated Inflation Insights: Disaggregation of inflation data and reporting is key to determining the strategies best positioned to serve key groups. While fluctuations in the inflation rate are frequently reported by expenditure category and geographic region, and 15 increasingly reported by income level and race/ethnicity16 , application of initiatives by the latter indicators are severely lacking. Philanthropy is uniquely placed to fund insight generation around disaggregated research findings to tailor initiatives for key populations highlighted in analysis.

- Financial Literacy & Access: As previously mentioned, lower-income households typically do not hold many, if any, savings and investments. This issue is often exacerbated during periods of inflation. For example, recent research showed a strong correlation between “financial literacy and inflation-induced changes in individuals’ personal finances”. Specifically, adults with very low levels of financial literacy were four times as likely to significantly reduce or completely stop retirement contributions during high periods of inflation in 2022, versus those with very high levels of financial literacy, who were able to maintain their retirement contributions.17 This evidence puts forth that inflation not only threatens needs in the short-term, but can also affect finances in the long-term.

Philanthropy can help improve financial literacy and trust, as well as improve access to products that protect the value of money as inflation rages. In combination with the social supports described above, equipping individuals with financial tools can enhance their ability to navigate inflationary pressures and provide a basis for financial decision-making during volatile times. This is well-understood by Next Gen Personal Finance (NGPF), a group working to democratize access to financial information, with a mission of ensuring that all US high school students are required to take a financial literacy course to graduate. In partnership with the California State Superintendent, NGPF is offering $1.4 million in grants to develop and deliver financial literacy courses in California public schools. The grants include stipends for teachers that become certified, as well as funds to hire a personal finance specialist for the largest school districts in the state.

It is key for philanthropic leaders to be aware of the disproportionate effect of inflation on their lower-income constituents; of the enduring nature of that impact even as top-line inflation figures reduce; and of the avenues at their disposal to kickstart a response via some of the above strategies, which represent only a partial snapshot of their available toolkit. Doing so will materially strengthen economic security at individual, household, and community levels even during times of financial tumult.

Citations

- Consumer prices up 9.1 percent over the year ended June 2022, largest increase in 40 years – US Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Summary findings, Food price outlook 2023 – USDA

- EIA expects U.S. gasoline and diesel retail prices to decline in 2023 and 2024 – EIA

- Inflation is falling but your health premiums may be about a soar. Here’s why – Los Angeles Times

- Monetary Policy and Price Stability – U.S. Federal Reserve

- Inflation could wreak vengeance on the world’s poor – Brookings

- Inflation’s wrath has Americans wrecking up high debt. What at risk households need to know – USA Today

- New Data Show Inflation Could Undermine Families of Color’s Financial Resilience. How Can Policymakers Help? – Urban Institute

- 2021 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households – FDIC

- Inflation and its impact on the poor in the era of COVID-19 – InterAmerican Development Bank

- Universal Cash Transfer and Inflation – Jones & Marinescu

- Getting cash transfer payments to recipient’s faster boosts household spending and stimulates the economy – Washington Center for Equitable Growth

- What have we learned about cash transfers? – Blogs World Bank

- The Importance of Competition for the American Economy – The White House

- State Inflation Tracker – US Congress Joint Economic Committee

- Inflation is higher for some demographic groups, report finds – Axios

- Financial Wellbeing and literacy in a high-inflation environment – TIAA Institute

Aislyn Orji is a Consultant at Camber Collective. She utilizes data-driven storytelling to support clients in advancing their strategic & operational goals. Prior to Camber, Aislyn worked as a global health researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics & Evaluation. In her time there, she developed methods for measuring the burden of various chronic & vertically transmitted diseases. She has further experience working with think tanks and nonprofits aimed at tackling issues of food insecurity, education, and homelessness.Aislyn earned an MPH concentrated in Health Metrics & Evaluation from the University of Washington. She also holds a BA in Health Sciences & minor in Sociology from Rice University, where she was a Trustee Distinguished Scholar. In her spare time, Aislyn enjoys exploring neighborhoods in new cities, and critiquing food with family & friends.

Marc Allen is a Director at Camber Collective and the Shared Prosperity Sector Lead, heading the firm’s Shared Prosperity portfolio. Drawing on his toolkit as a strategist and former policy attorney, Marc leads teams working to strengthen and reimagine our economic and democratic systems. His experience spans strategy and investment design, human-centered research/insights, and coalition-building services for philanthropies, government agencies, multilateral institutions, nonprofits, and socially-invested corporations. More broadly, Marc guides the effectiveness of executive teams in mission-driven organizations, helping to advance their theories of impact, program design, business models, and cultures of belonging.