As we reduce emissions, let’s not forget about the impact of climate change on health

Climate change is affecting the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the quality of food we eat. Over the past decades, it contributed to a rapid increase in asthma cases and allergies and the spread of mosquitoes to higher hemisphere regions, with the US seeing the first cases of local malaria transmission in two decades [1]. The WHO (World Health Organization) projects that, all else equal, between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year from heat stress, malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress [2].

Extreme climate events have significantly increased over the past 50 years

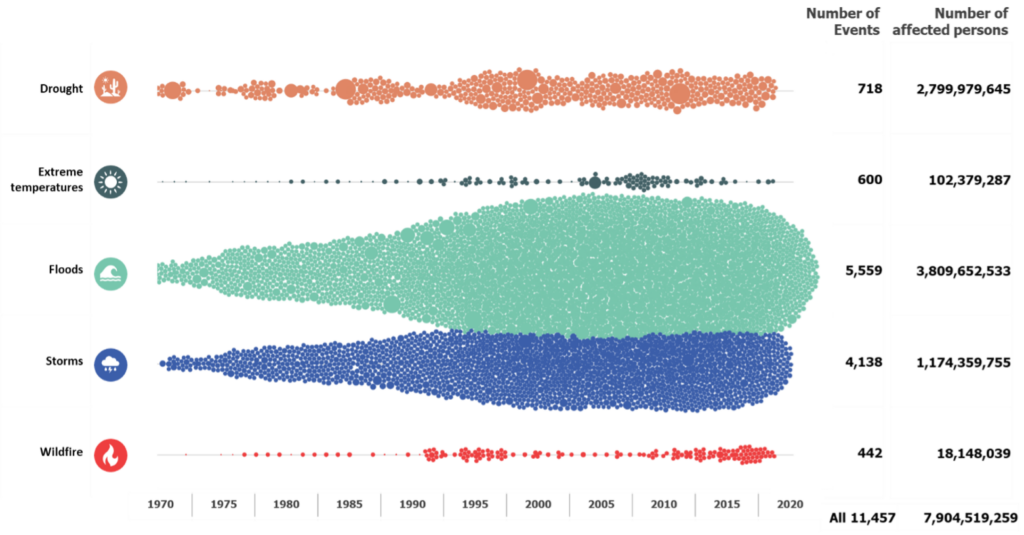

Over the recent decades, extreme climate events have significantly increased, primarily floods, storms, and wildfires. This affects millions through population displacement, socioeconomic shocks, direct mortality, and health impact (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of extreme weather events and people affected [4].

Note: Each dot represents an event; the circle size represents the number of affected persons.

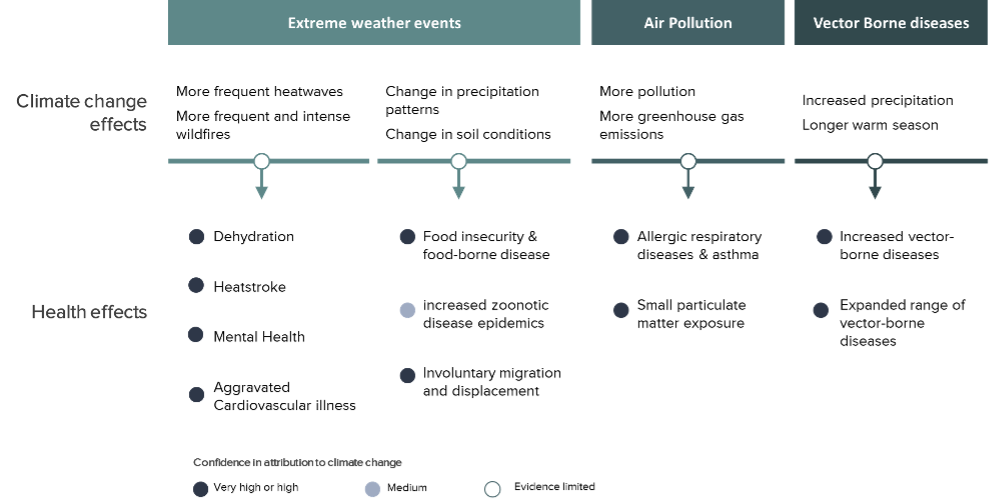

According to IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) scenarios, global temperatures will continue to rise, causing more adverse effects on human health. The burden of many climate-sensitive health risks is projected to be greater at an increase of 2 ◦C above pre-industrial temperatures than at 1.5 ◦C., highlighting the sensitivity of health conditions to minor changes in global temperatures [3]. We outline examples of crucial health conditions expected to exacerbate if we continue our current trajectory in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Illustrative health effects of climate change [5]

Global warming with unequal local impacts

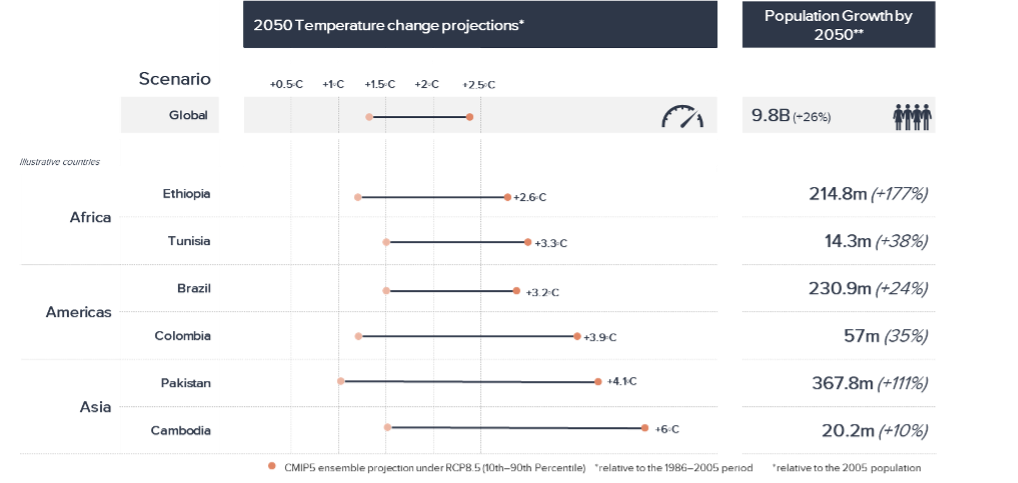

While global warming is measured against the global average target of 1.5◦C, the local impact varies significantly, with some regions bearing a significant burden. More countries are undertaking better vulnerability and adaptation assessments to understand the health risks they will face as temperatures rise. These analyses have highlighted the most vulnerable populations, often the elders, children, and people living in remote areas [7].

We have highlighted below in Figure 3 the projected temperature increase in select countries, highlighting the global disparities. Even the national average hides vast differences in the sub-national regions, with some areas extremely vulnerable to changing conditions. Rapid projected population growth in most countries will also contribute substantially to the number of people affected by temperature rises and extreme weather events.

Figure 3. Projected temperature changes under different climate-change scenarios and population growth between current and 2050. [8] [9]

What are we doing about it: Current funding trails projected need

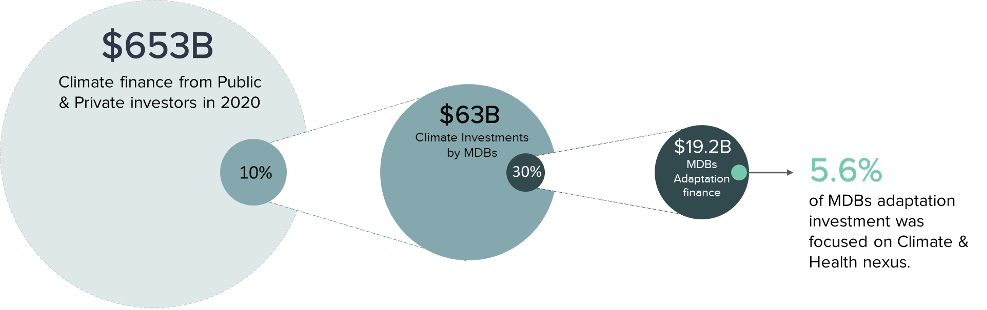

While the scientific community and country priorities emphasize the growing challenge that the globe faces related to climate and health, funding commitments at the intersection of these sectors have continued to trail behind the projected need.

Development finance institutions (DFIs) have increased their commitments to climate in recent years and, on average, committed to nearly doubling their spending on climate from 2020 to 2025 [11]. Certain DFIs have even made ambitious commitments until 2030, including the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank (WBG), which have committed to dedicating 75 percent of commitments to climate finance by then. While spending on climate has been increasing, the share of spending to mitigate health impact remains very low at under 6% of climate adaptation funding [10].

Figure 4. Breakdown of Adaptation spending by major MDBs in 2020/2021 [10][11].

Despite the recent push by some major development finance institutions to increase overall climate spending and adaptation spending as a percentage of this amount, total mitigation spending by multilateral development banks (MDBs) was still over three times that of adaptation spending in 2021[11].

The focus of development finance institutions on mitigation activity (vis-a-vis adaptation) or the importance of CO2 reduction as the defining metric to measure the impact of climate projects may explain their hesitation to shift funding into the climate-health nexus.

On the health side, DFIs bolstered their spending during the COVID-19 pandemic. Across four major MDB (WB, IDB, AfDB, ADB), health funding rose 3-fold from $3.8 billion in 2018 to $12.1B in 2021 [12]. Despite this pandemic-driven increase, the overall health sector constitutes a small portion of total funding and trends between 5% and 15% for most bilateral and multilateral institutions [13].

Despite the recent momentum in the climate and health sectors individually, funding at the intersection of climate and health has remained stagnant. It is not yet a stated focus of most funders.

The philanthropic sector has followed a similar trend as development finance institutions. While many philanthropies dedicate energy and funds to the climate and health sectors individually, few of these institutions have declared a focus at the nexus of the two. Wellcome Trust is one of few large foundations with an expressed focus on funding climate-health interventions, communicating the intersection as one of their three focus areas related to health [13]. This presents an opportunity for other foundations to direct capital to an underfunded sector to catalyze additional investments.

What’s holding us back: Key challenges to increase capital commitments

Funders face several challenges when deciding to invest in projects at the intersection of climate and health; if addressed, there is potential to vitalize commitments in the space [13]. These challenges range from a need for a shared definition and impact metrics for climate-health investments to a lack of robust evidence across these interventions.

Thoughts on a way forward

Considering the challenges depicted above, a range of actions can be undertaken to address the key issues hindering further commitments to climate-health initiatives.

Here are three recommendations to address the challenges outlined [13]:

The upcoming COP28 is a promising opportunity to delve deeper into this topic as it is the first COP conference that includes an entire day dedicated to the health sector. This global convening presents a unique occasion to gather key stakeholders to identify solutions to these challenges, garner momentum, and solidify commitments at the climate-health nexus.

Citations

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/27/health/us-malaria-mosquitoes.html [2] Climate change and health (who.int) [3] Health risks of warming of 1.5″00B0`0C, 2″00B0`0C, and higher, above pre-industrial temperatures (iop.org) [4] Data from EM-DAT. The International Disaster Database; Graphic produced with RAW Graphics. [6] Data from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/chapter/chapter-7/; graphic produced in Microsoft PowerPoint. [7] Climate change and health: vulnerability and adaptation assessment (who.int) [8] Climate Risk Country Profiles | Climate Change Knowledge Portal (worldbank.org) [9] World Population Dashboard (unfpa.org) [10] How much bilateral and multilateral climate adaptation finance is targeting the health sector? A scoping review of official development assistance data between 2009–2019 – PMC (nih.gov) citing Lancet Countdown data. [11] 2021 Joint report on multilateral development banks’ Climate finance (eib.org) [12] Microsoft Word – 2023-04 Making it work – role of MDBs – final.docx (actionsantemondiale.fr)Melissa Flores leverages her background in quantitative analysis and research to support clients’ strategic decision-making centered around social impact. Prior to Camber, Melissa worked as consultant at the UN World Food Programme, providing operational and programmatic support to the organization’s global food security monitoring initiative. Melissa began her career as a financial consultant, working on risk mitigation strategies for Consumer and Healthcare clients in the United States. She holds an M.A. in International Development from Sciences Po’s Paris School of International Affairs and a B.A. in Applied Mathematics from Harvard University.

Abdel Agadazi is a Camber Collective alum. While with the firm, he worked with clients on their strategy and investment planning via data-driven decision-making and market analysis. Prior to Camber, Abdel led consulting engagements at Accenture, supporting global clients on their digital transformation journey. He began his career building technology systems for optometrists and healthcare clients in the United States. Abdel is also involved in supporting entrepreneurs in Europe and Africa through growth and operational advice. He holds an MBA from INSEAD and a Master’s in advanced analytics from IMT Atlantique, a top-tier French engineering school. Abdel grew up in Lomé, and he enjoys cooking and playing basketball. Our Paris office mates look forward to seeing him strolling the streets as an amateur photographer.