Food Security, Urban Migration, Healthcare, Economic Wellbeing & Population Displacement

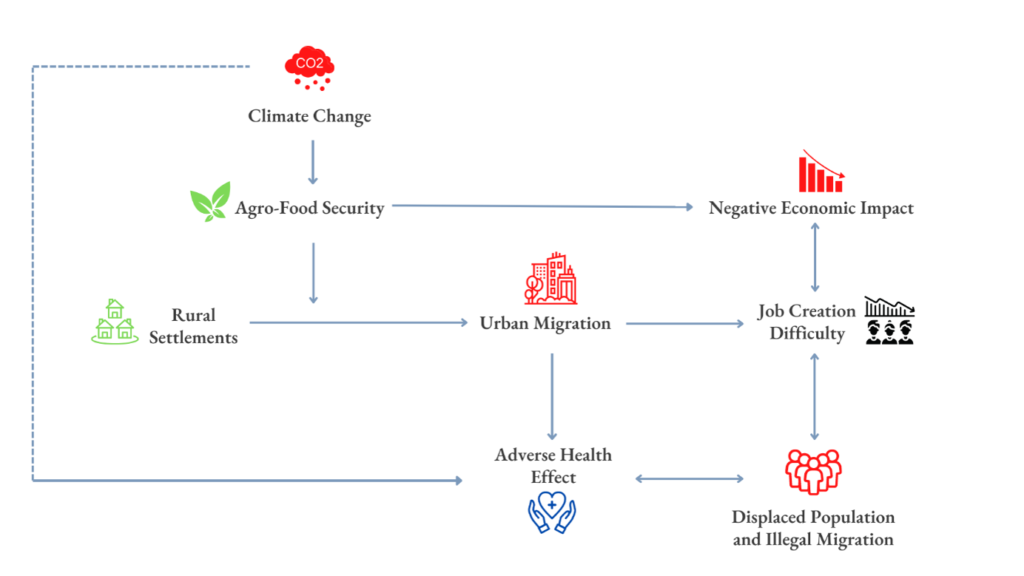

The Global South, particularly countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) face the highest risk of climate vulnerability and developmental issues exacerbated by climate change. For example, the African continent contributes only a small percentage of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but its inhabitants are among the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change and have the least infrastructure for climate resilience. These issues brought about by climate change impact local environments and trigger several serious problems that threaten the livelihood of most residents. If progressively left unchecked, these issues will undoubtedly create a near-term catastrophic retrogression in the region’s economy.

According to a study on the effects of climate change, a mere 1 °C increase in temperature in developing countries has been found to cause 2.66% lower growth in agricultural output (1). This factor alone leads to, for each degree of warming, an estimated average 1.3 percentage point-drop in economic growth.

Survival on the Line

To put it simply: as humans, our survival is based on the availability and access to Food, Clean Air, Water and Shelter. With any one of these basic needs unmet, humanity can no longer survive. Indeed, climate change threatens the availability of these resources. Of course, this is not new news – but it is urgent. A great deal must be done to return to a state of equilibrium. In rural areas of developing countries, the impacts of climate change dangerously affect the agricultural industry. Particularly, in the SSA region, farming and agriculture are the sectors at the forefront of food security and sustainable jobs. The sector also employs roughly two-thirds of the regional labor force.

The yield potential of many African crops is however not fully realized, due to over-reliance on resources such as inadequate (rain)water and a dearth of nutrients to boost crop production. Rainfed agriculture yields fewer crops, further contributing to a stunted agro sector in Africa. This dearth impacts both livelihood and survival. In addition to creating drag on local economies, poor crop yields force smallholder farmers to seek additional or alternative sources of livelihood, initiating a cascade effect that leads to forced migration to now over-populated urban areas and cities.

While urbanization is generally beneficial, most of Africa’s city dwellers live in extreme poverty—and economic suffering that is likely to increase as climate change worsens. As urbanization rates increase in some developing countries, we are beginning to see a corollary of negative wellness outcomes such as poor nutrition, pollution-related illnesses such as respiratory disease, a rise in communicable diseases, poor sanitation, and uninhabitable housing conditions. (2)

These detriments further strain available resources in urban areas. For example, Lagos is one of the world’s 10 largest cities, sprawling across 1,000 sq. km and housing 20 million inhabitants in a largely chaotic and impoverished setting. Most residents live in informal settlements, also known as slums. With no holistic water or sanitation system, disorganized transportation and extreme traffic congestion, and massive environmental issues such as noise and air pollution, this coastal city is a cataclysm waiting to happen. Indeed, it is predicted that by 2100, Lagos will be the world’s largest city, squashing 100 million people in a grave environmental and social setting.

The predicted major health problems of Lagos residents are further exacerbated by the generally poor quality of health service delivery. Less than half the continent’s population has access to health care, and family planning services are unavailable to half the continent’s women and girls.

While private healthcare is available to some, its high cost makes it unattainable to most people, as the region’s largest social challenges include unemployment and vulnerable employment, which are often linked with the effects of climate change. These challenges are growing in severity, as population growth remains high, and poverty and unemployment are also on the rise. Likewise, climate vulnerability is aggravated as there are little to no infrastructure for climate adaptation.

Less than half the continent’s population has access to health care, and family planning services are unavailable to half the continent’s women and girls.

Job Demand Outweighs Supply

The World Bank reported in 2013 that there would be 10 million new entrants to the labor force every year. As of 2017, other institutions—such as the International Labor Organization (ILO)—have reported that there are at least 20 million young people looking for work every year. The number of job seekers on the African continent is increasing significantly and despite all efforts so far to create more formal jobs for young people, very few of them currently stand a chance of finding employment. The statistics are stark: each year 20 million young people enter the labor market, with only a few gaining formal employment. On the potentially brighter side the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that if the sector continues to develop, renewable energy jobs could employ 43 million people by 2050.

An example of this discrepancy between job supply and demand can be seen in the country of Uganda. 400,000 young Ugandans enter the job market annually, competing for approximately 52,000 formal jobs.(3) For girls and young women, the job attainment situation is particularly dire. With fewer opportunities to work in the formal labor market, young women are often forced to seek work in the informal economy. As previously noted, climate change continues to disrupt agricultural productivity and supply chains, leading to further regional displacement from rural regions and larger cities alike, with many having no choice but to undertake the long and treacherous journey of (illegal) migration to the EU.

A Moral Obligation to Act

The Global North is responsible for 92% of excess global carbon emissions, according to a study published in The Lancet Planetary Health (4). The findings, based on the idea that the atmosphere is part of the global commons, are worrying considering many experts consider it critical to protect against global warming and climate change. There is a moral obligation to deliver upon the Polluters Pay Principle (5). It spurs sustainable development through the development of innovative strategies for climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience for developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in rural regions to ensure sustainable development.

Each further delay in redressing the detriments of climate development disequilibrium will result in future situational overload, making climate mitigation even more difficult to reach, and destroying the wellbeing and livelihood of millions of people in the not-very-distant future. For those who remain unswayed by the humanitarian imperative, a parallel emergency, based on economic is also evident: delay or lack of climate investment, infrastructure, and innovation applications in the rural and super-urban and rural areas will only make sustainable transition even more exigent. Tangentially, it will also make change, which will become necessary one way another, extremely more expensive.

Over the next series of blog posts, we will further examine the intersection and impact of climate induced changes and development.

Dr. Chidiebere E.X. Ikejemba is the Director of Climate & Environment at Camber Collective. His body of work focuses on climate equity and justice, building resilient climate-smart development programs, strengthening political will for urgent climate change action and many other levers of activation. His theory of impact operates across both the upstream and downstream of a systems chain. that encompasses investment, agriculture & food security, migration, economic & rural development, climate education, waste management (circularity), healthcare, corruption and democracy, energy access, gender inclusion and other dimensions. The circularity of Camber’s approach and theory of influence is, we believe, the most congruous path to balancing economic reality and humanitarianism.

Sources

1 – Dell, M., Jones, B. F., & Olken, B. A. (2012). Temperature Shocks and Economic Growth: Evidence from the Last Half Century. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 66-95.

2 – Kuddus, A., Tynan, E., & McBryde, E. (2020). Urbanization: a problem for the rich and the poor? Public Health Review

3 – Kappel, R. (2021). Africa’s Employment Challenges – The Ever-Widening Gap. Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung e.V.

4 – Hickel, J. (2020). Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary. The Lancet Planetary Health, 399-404.

5 – The Polluters Pay Principle is the commonly accepted practice that those who produce pollution should bear the costs of managing it to prevent damage to human health or the environment.