Introduction

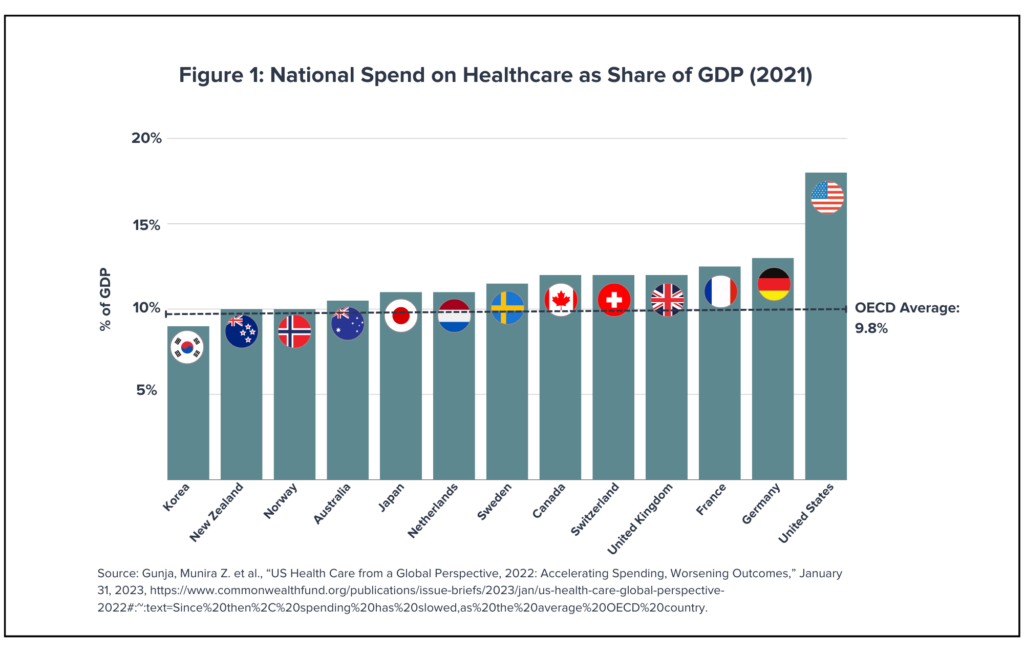

Despite the fact that the US spends approximately 18% of GDP on healthcare—almost twice as much as the average Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) country—our healthcare system is riddled with problems, from widespread inequities to poor outcomes to barriers to care (see Figure 1).[1] In this tripart series, we discuss three specific types of barriers to care for those living with severe mental illness—macroeconomic, legislative, and capacity—examining the nature of these access barriers and how they impact overall outcomes. In this second installment of the series, we highlight a legislative barrier to accessing mental health services that is deeply rooted in the Medicaid program.

Overview of the IMD Exclusion

Authorized under Title XIX of the Social Security Act and signed into law in 1965, the Medicare and Medicaid Act was designed to help create a social safety net for the most vulnerable members of American society, providing health coverage to adults over the age of 65, younger adults with disabilities, and low-income adults.[2] While this social safety net is far from perfect, one of the most pronounced gaps involves the institution for mental diseases (IMD) exclusion, which has been in place since Medicaid’s inception.

Medicaid is a joint federal-state insurance plan whereby states administer the program in accordance with federal regulations and the federal government makes matching payments to the states in a cost-sharing arrangement. However, the exclusion prohibits the federal government from making these matching payments for services provided in certain types of settings to Medicaid beneficiaries between the ages of 21 and 64, notably IMDs.[3] An IMD is defined as a hospital, nursing facility, or other institutional setting with more than 16 beds that is primarily engaged in providing psychiatric treatment and care to people living with mental illness, including substance use disorders, where the “primarily engaged in” threshold is met when more than 50% of a facility’s patients receive mental health services.[4] The exclusion applies to both behavioral health- and standard medical-related care as well as to services that happen to be provided outside an IMD to a current IMD resident.[5]

A New Model of Care: The Combined Impact of the IMD Exclusion and Deinstitutionalization

The IMD exclusion was designed to shift the cost of psychiatric care from the federal government to the states as well as discourage the treatment of mental illness via large institutional settings like long-stay state psychiatric hospitals.[6] The enactment of the IMD exclusion coincided with and likely helped accelerate deinstitutionalization, the movement popular in the 1950s and 1960s to redefine mental health treatment, with the intent of replacing care in long-stay psychiatric facilities with community-based care. This marked shift in perspective regarding the best approach to treating mental health issues and the subsequent change to the accepted model of care was aided by the development of first-generation antidepressant and antipsychotic medications.

For context, between 1970 and 2018, the number of state psychiatric beds decreased by 84% across the US, though these losses have been offset to a small degree by the increase in private psychiatric hospital beds in recent decades.[7] Currently, the US has approximately 12 state psychiatric hospital beds per 100,000 people compared to nearly 340 beds per 100,000 in the mid-1950s.[8] This drastic decrease in the number of beds available in state psychiatric hospitals reflects the historical reliance on institutionalization juxtaposed against the current focus on providing more community-based care.

Impact of the IMD Exclusion

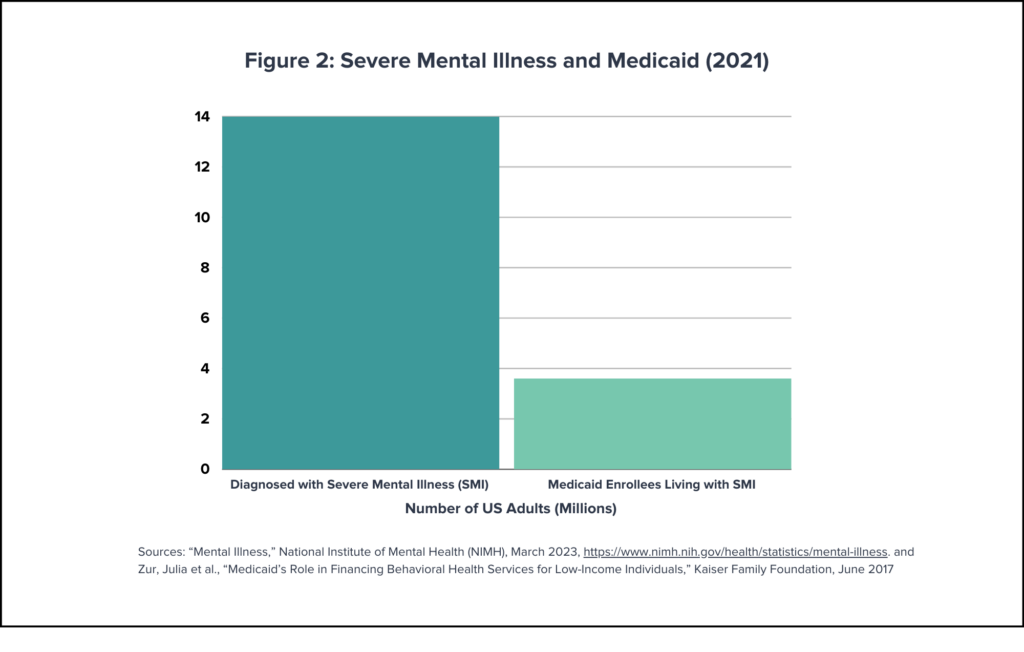

It is estimated that more than 14 million American adults suffer from severe mental illness (SMI) such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia that significantly interferes with their ability to partake in major life activities and sometimes requires hospitalization.[9] Approximately one-quarter of US adults living with SMI are covered by Medicaid.[10],[11] The IMD exclusion thus holds the potential to impact the care received by the approximately 3.6 million adult Medicaid enrollees living with SMI (see Figure 2).

The very nature of the IMD exclusion has created significant barriers to care, with its critics deriding it as discriminatory because it can prevent Medicaid patients with severe mental illness from being able to access the full range of treatment options they may need, specifically inpatient behavioral health services. This exclusion is the only aspect of federal Medicaid law that prohibits payment for medically necessary services simply due to the facility type providing the care.[12]

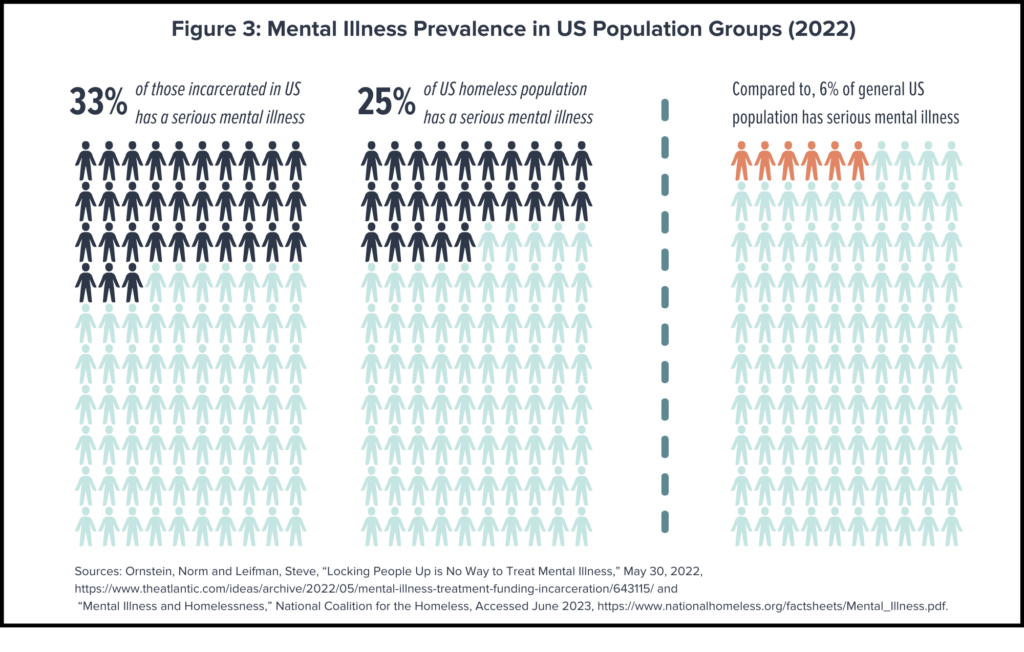

The impetus behind the move to deinstitutionalize mental health patients was noble in many ways, grounded in a desire to treat people with greater humanity; however, cost saving considerations cannot be ignored as a driving force behind the movement. Regardless of the motives, the implementation was flawed, chiefly because the community-based care infrastructure was simply not robust enough to support the nation’s mental health needs (and many would argue that it is still not robust enough).[13] As a result, many patients discharged from state mental hospitals were simply relocated to other institutional acute care settings, diverted to the criminal justice system, or directed to homeless shelters, an outcome that is indicative of a community-based system ill-equipped to serve this vulnerable patient population.[14] It is estimated that up to one third of those incarcerated and up to 25% of the homeless population has a serious mental illness, compared with 6% of the general population (see Figure 3).[15],[16]

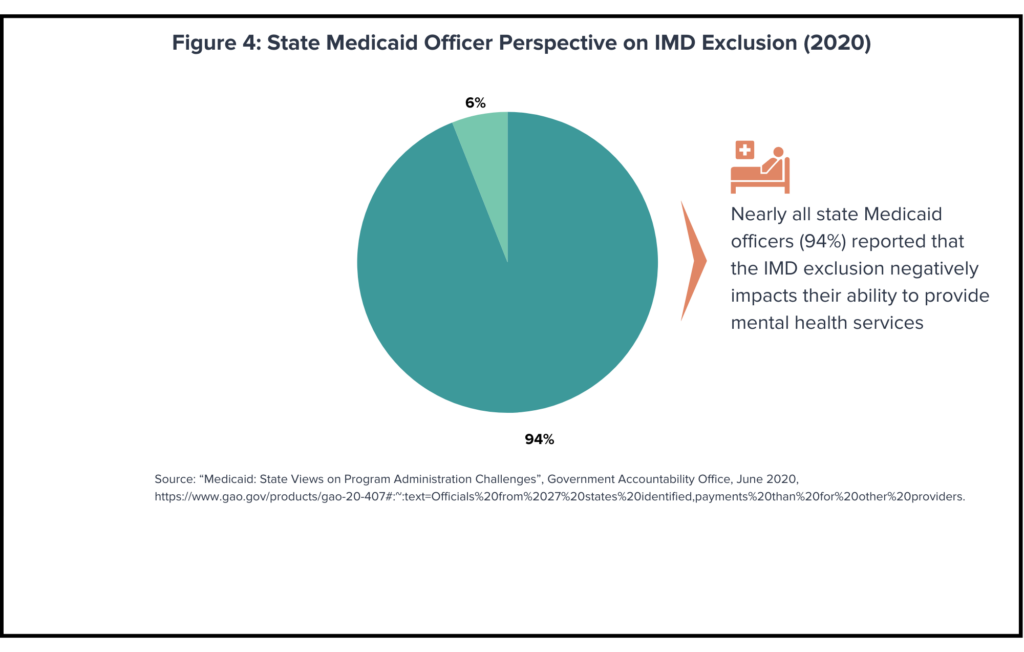

The flawed implementation of the deinstitutionalization movement that the IMD exclusion helped accelerate is also apparent when examining the availability of inpatient psychiatric beds state by state. Nearly one-third of states provide fewer inpatient beds than the estimated need. [17] While the IMD exclusion is not the only contributing factor to the state-level mismatch between inpatient bed supply and demand, it likely plays a contributing role in the undersupply of beds (weighted for relative state population) evident in states such as Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, among others. A 2020 Government Accountability Office (GAO) survey found that 47 of 50 state Medicaid officers reported that the exclusion impedes their ability to provide the full continuum of care, including the provision of sufficient bed capacity (see Figure 4).[18]

The IMD exclusion is one of the key drivers behind the “boarding” problem plaguing hospitals where patients with psychiatric symptoms are admitted to a hospital, but left in the emergency department, for example, because no suitable psychiatric care beds are available. In a 2008 survey of 328 emergency department directors conducted by the American College of Emergency Physicians, nearly 80% reported boarding psychiatric patients; the number of public psychiatric beds has declined since the time of that survey, likely exacerbating the boarding problem.[19]

Ways to Navigate Around the IMD Exclusion

During the last decade, certain avenues have become available for states to secure reimbursement for care provided in an institution for mental diseases. For example, states have leveraged IMD exclusion workarounds such as the use of “in lieu of” authority to access federal Medicaid funds to cover IMD inpatient services in those states with capitated managed care delivery systems or the use of lump sum disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments to help cover uncompensated care at IMDs.[20] Additionally, between October 2019 and September 2023, an additional option was made available to states under the 2018 Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) ACT. This state plan option provided up to 30 days of coverage over a 12-month period for adult Medicaid enrollees with at least one substance use disorder (SUD) treated at an IMD.[21]

Furthermore, the Affordable Care Act established a pilot program—a section 1115 demonstration in Medicaid parlance—that removed the exclusion for certain facilities to assess whether reimbursing psychiatric services provided in an IMD setting could deliver improved care at a decreased cost. The demonstration proved successful and in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services (CMS) finalized a rule that allows Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) to receive federal reimbursement for short-term care (e.g., less than 15 days per month) provided to non-geriatric adults in IMDs.[22] However, it is important to note that the section 1115 demonstrations are often time-delimited and state-specific and thus, do not provide a long-term solution to the IMD exclusion.

Looking Ahead

While such exemptions to the IMD exclusion have proven helpful in recent years, too many people suffering from chronic and acute mental illness still cannot access the care they need. Since the exclusion is codified in the federal Medicaid statute, an act of Congress would be required to either eliminate or otherwise make any changes to it such as increasing the bed limit so that the regulation would no longer apply to larger facilities. There has been an uptick in legislative activity related to the IMD exclusion in recent years, with ten bills introduced that would either fully repeal the exclusion or amend it in some way during the past two Congresses, providing some hope that a meaningful change to this discriminatory rule is on the horizon.[23]

The removal of the IMD exclusion would significantly impact the federal Medicaid budget. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that eliminating the IMD exclusion would increase federal expenditures by approximately $38 billion between 2024 and 2033, though some of this outlay would likely be offset by decreased emergency department and general hospital inpatient spending.[24] The state dollars previously spent on emergency and inpatient care could be reallocated to support the expansion of community-based services.[25] The CBO also projected that it would cost between $155 million and $560 million on net to make the SUPPORT Act state plan option a permanent fixture over the same ten-year period; the range of estimates reflects multiple implementation pathways for making the state plan option permanent.[26]

Eliminating the exclusion or amending it in a substantive way would not only remove a discriminatory policy from the Medicaid program, but also would effectively eradicate a key barrier to accessing mental healthcare that disproportionately impacts more vulnerable patient populations. It is important to note that if the IMD exclusion is overturned, providers would likely need to add capacity to ensure that the barrier to access does not simply evolve from one that is legislative into one that is infrastructural. Though the budgetary impact must be considered, many experts in the field firmly believe that eliminating the IMD exclusion and enabling states to more easily access federal Medicaid funds for inpatient mental health and substance use treatment could help successfully address a barrier to accessing care and greatly improve the overall health and wellbeing of people living with mental illness.[27]

Read Part One

Notes

[1] Gunja, Munira Z. et al., “US Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes,” January 31, 2023, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022#:~:text=Since%20then%2C%20spending%20has%20slowed,as%20the%20average%20OECD%20country.

[2] “Program History,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Accessed January 5, 2024, https://www.medicaid.gov/about-us/program-history/index.html#:~:text=Authorized%20by%20Title%20XIX%20of,coverage%20for%20low%2Dincome%20people.

[3] “Budgetary Effects of Policies to Modify or Eliminate Medicaid’s Institutions for Mental Diseases Exclusion,” Congressional Budget Office, April 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59071#:~:text=Under%20a%20policy%20known%20as,certain%20types%20of%20inpatient%20facilities.

[4] “Payment for services in institutions for mental diseases,” Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/payment-for-services-in-institutions-for-mental-diseases-imds/.

[5] Eide, Stephen and Gorman, Carolyn D., “Medicaid’s IMD Exclusion: The Case for Repeal,” February 23, 2021, https://manhattan.institute/article/medicaids-imd-exclusion-the-case-for-repeal#notes.

[6] “The Psychiatric Bed Crisis in the US: Understanding the Problem and Moving Toward Solutions,” American Psychiatric Association, May 2022, https://www.psychiatry.org/getmedia/81f685f1-036e-4311-8dfc-e13ac425380f/APA-Psychiatric-Bed-Crisis-Report-Full.pdf.

[7] Lutterman, Ted, “Trends in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity: United States and Each State, 1970 to 2018,” National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, September 2022, https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/Trends-in-Psychiatric-Inpatient-Capacity_United-States%20_1970-2018_NASMHPD-2.pdf.

[8] “The Psychiatric Bed Crisis in the US: Understanding the Problem and Moving Toward Solutions”.

[9] “Mental Illness,” National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), March 2023, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.

[10] Zur, Julia et al., “Medicaid’s Role in Financing Behavioral Health Services for Low-Income Individuals,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2017

[11] McMullen, Erin K. and Roach, Melinda Becker, “Behavioral Health in Medicaid,” MACPAC (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission), Sept. 24, 2020.

[12] “Medicaid: IMD Exclusion,” National Alliance on Mental Illness, Accessed February 6, 2024, https://www.nami.org/Advocacy/Policy-Priorities/Improving-Health/Medicaid-IMD-Exclusion.

[13] ibid[14] “The Psychiatric Bed Crisis in the US: Understanding the Problem and Moving Toward Solutions”.

[15] Ornstein, Norm and Leifman, Steve, “Locking People Up is No Way to Treat Mental Illness,” May 30, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/05/mental-illness-treatment-funding-incarceration/643115/.

[16] “Mental Illness and Homelessness,” National Coalition for the Homeless, Accessed June 2023, https://www.nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/Mental_Illness.pdf.

[17] González-Caballero, Juan Luis et al., “Benchmarks for Needed Psychiatric Beds for the United States: A Test of a Predictive Analytics Model,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, November 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8625568/#B1-ijerph-18-12205.

[18] “Medicaid: State Views on Program Administration Challenges”, Government Accountability Office, June 2020, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-407#:~:text=Officials%20from%2027%20states%20identified,payments%20than%20for%20other%20providers.

[19] Eide, Stephen and Gorman, Carolyn D.

[20] Musumeci, MaryBeth et al., “State Options for Medicaid Coverage of Inpatient Behavioral Health Services,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 6, 2019, https://www.kff.org/report-section/state-options-for-medicaid-coverage-of-inpatient-behavioral-health-services-report/.

[21] Houston, Megan B., “Medicaid’s Institution for Mental Diseases (IMD) Exclusion,” Congressional Research Service, October 5, 2023.

[22] “The Medicaid IMD Exclusion and Mental Illness Discrimination,” Treatment Advocacy Center, August 2016, https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/component/content/article/220-learn-more-about/3952-the-medicaid-imd-exclusion-and-mental-illness-discrimination-.

[23] Houston, Megan B.

[24] Budgetary Effects of Policies to Modify or Eliminate Medicaid’s Institutions for Mental Diseases Exclusion,” Congressional Budget Office, April 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59071#:~:text=Under%20a%20policy%20known%20as,certain%20types%20of%20inpatient%20facilities.

[25] Musumeci, MaryBeth et al.

[26] Budgetary Effects of Policies to Modify or Eliminate Medicaid’s Institutions for Mental Diseases Exclusion.

[27] Ibid.

Notes

Kim Langenhahn draws on more than 15 years of consulting, operational, and startup experience in the domestic and international health and nonprofit sectors to help organizations navigate complex issues, operate more effectively, and deliver greater impact. During the course of her career, Kim has helped numerous healthcare organizations tackle a variety of strategic challenges such as scaling Terrapin Pharmacy’s remote medication adherence system, launching a MENA-focused healthcare incubator, devising system-wide strategy for the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health as part of PwC’s consulting practice, and developing a market forecast for a pharmaceutical company alongside her L.E.K. Consulting colleagues. She is also the Cofounder of a small social enterprise that she runs with her family

Kim earned a Master of Business Administration and a Master of Public Policy from the University of Chicago as well as a Master of Science in Quantitative Management and a Bachelor of Arts from Duke University. An avid traveler, reader, bread baker, ice cream churner, and (aspiring) cheese maker, she also enjoys helping her husband tend to their rooftop garden and vermiculture operation. She currently resides in Washington, D.C.

As Camber Collective’s Director of Impact and Equity Rozella Kennedy helps direct the firm’s internal Impact, Equity, and Belonging work as well as the external practice. Her theory of impact seeks to leverage equitable values to influence and impact the humanitarian, development, philanthropic, and social impact sectors. The long focus is to expand awareness and practice in local and global post-colonial contexts. Rozella is also the creator of Brave Sis Project, a lifestyle brand using narrative and social engagement to uplift BIPOC women in U.S. history as a tool for learning, growth, celebration, and equity allyship; her book “Our Brave Foremothers: Celebrating 100 Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous Women Who Changed the Course of History” was published by Workman Press in Spring, 2023.