Summary

The Economic Mobility space in the US is most heavily focused on mobility from poverty at present. It is therefore better referred to as the ‘Mobility from Poverty’ space, for maximum resonance with stakeholders.

The goals of the organizations in this space are too divergent for Mobility from Poverty to be construed as a singular field. It can be more accurately understood as an ‘umbrella’ spanning three distinct fields, each angled towards a unique objective.

Stakeholders seeking to impact the Mobility from Poverty space in the US should therefore strive to understand the scope and primary objective of each of these three fields; deploy their resources to address the needs of the field (or fields) that align most closely with their own mission; and understand that ultimately, mobility from poverty is best advanced by ensuring that all three fields progress to full maturity.

Background

In 2021, Camber Collective set out to define the Mobility from Poverty space in the US; evaluate the current state of this space; and identify its future growth needs. This article focuses on learnings from the first phase of work, which served to define and make sense of the Mobility from Poverty space. It also introduces the field evaluation framework by which to evaluate these fields most holistically. Our subsequent article[MA1] summarizes the current maturity level and growth needs of each field.

‘Mobility from Poverty’ may be a more inclusive label for the space than ‘Economic Mobility’

Because the term ‘economic mobility’ is often interpreted by stakeholders as part of a growing trend to ‘ignore’ the age-old challenge of poverty, many stakeholders stated that they would not necessarily consider themselves part of an ‘economic mobility’ space if termed as such. However, ‘Mobility from Poverty’ surfaced as a more inclusive name to attribute to this general area of work, and more closely reflective of the field’s current focus on transitioning individuals and communities out of a state of economic marginalization.

Mobility from Poverty cannot be construed as a singular ‘field’

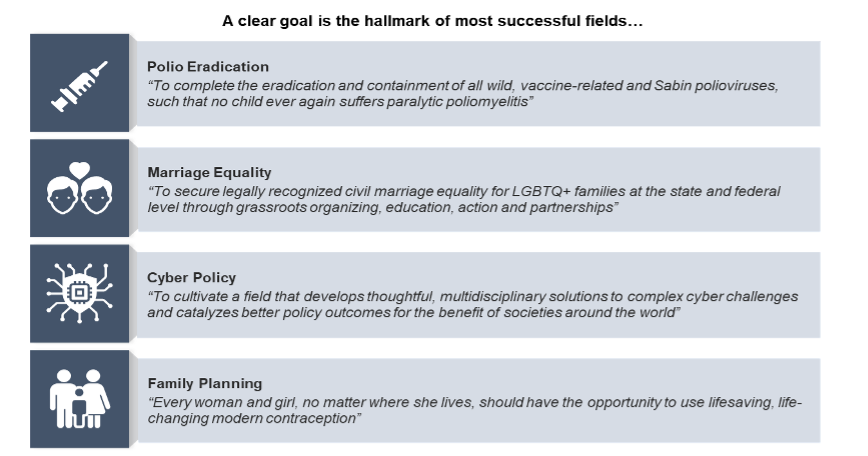

One of the defining features of nearly all successful fields is the existence of a clear and unifying societal goal, which stakeholders in that field agree to work towards together. Examples of this – including several successful fields Camber has served as a strategic advisor to in the past – are illustrated below:

Yet, defining a singular goal does not appear possible for the Mobility from Poverty space, for at least three reasons.

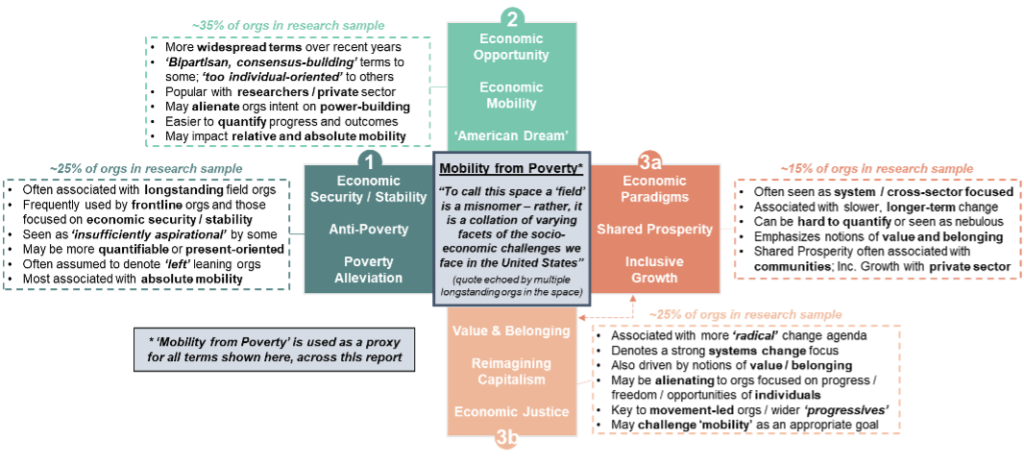

First, by simply surveying the variety of goals cited by the organizations making a public commitment to Mobility from Poverty, it is immediately apparent that there is no completely unifying objective in this space. Instead, stakeholders focus on differing facets of the Mobility from Poverty conundrum, using 3-4 different categories of terms to describe their visions (categories 3a and 3b are frequently amalgamated):

Second, to compound these challenges, stakeholders also adopt differing definitions of economic mobility as their primary metric for tracking impact. The various definitions of economic mobility – and the differing interest areas and agendas they reflect – are explained in our previous article on the subject.

Third, advancing mobility from poverty requires sustained progress across at least 12 different issue areas, which were identified in our research as the most common focal areas for stakeholders active in this space. They are listed here in alphabetical order (not in order of relevance): Criminal Justice, Democracy & Civic Engagement, Economic Principles, Education & Skills, Family Welfare, Financial Wellbeing, Housing, Health, Infrastructure, Network-Building, Safety Nets, and Work & Income.

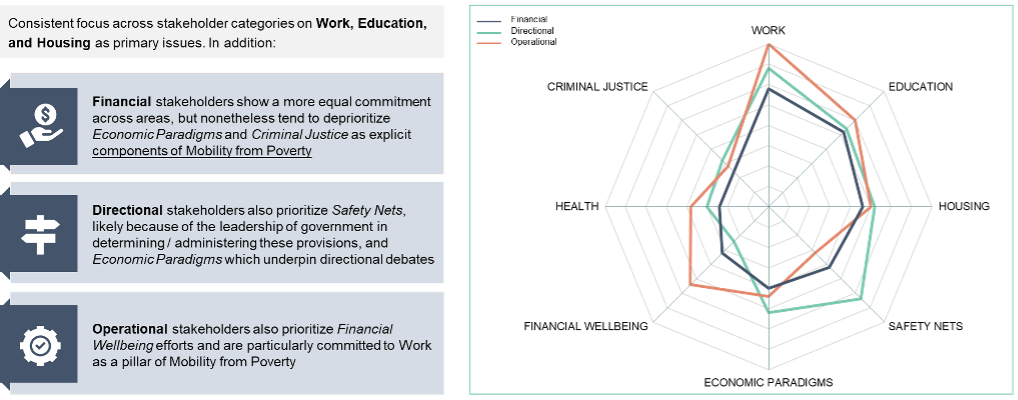

The fact that such a vast spectrum of issue areas is relevant to mobility from poverty presents unique challenges to field-building – in part because it requires stakeholders to undertake collective visioning across the traditional siloes of issue areas, and in part because if stakeholders were forced to act as a singular ‘field’, they likely would struggle to agree on which issue areas to prioritize beyond Work, Education, and to a lesser degree, Housing. The graphic below evidences the inconsistent focus given by the 140 stakeholders we studied to (a subset of) the 12 issue areas listed above:

The economic mobility space is better understood as a compilation of three fields

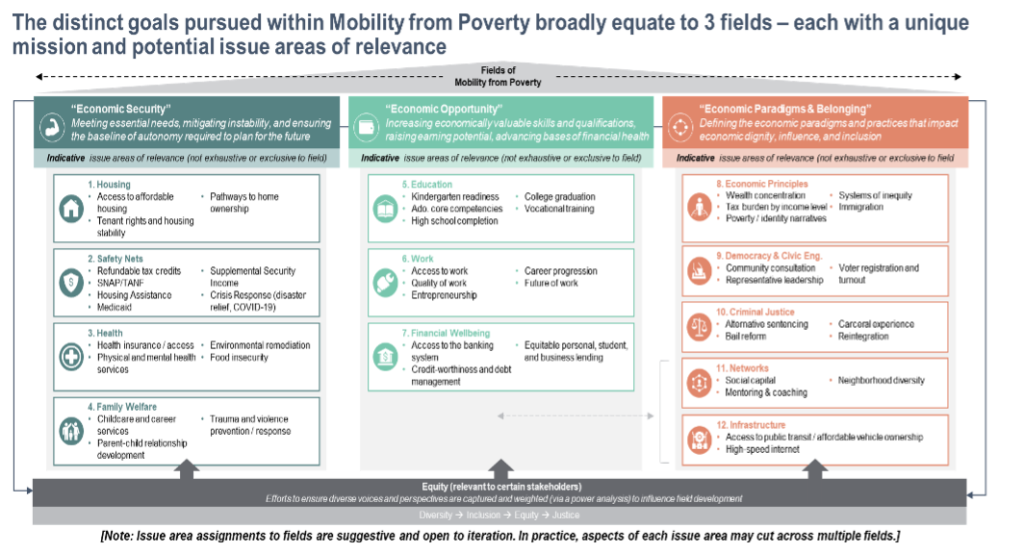

Recognizing the innate fragmentation of the Mobility from Poverty space, we therefore proceeded to triangulate the various sources of quantitative and qualitative data we generated from our research (see Background section above) to came to understand – thanks to clear feedback from stakeholders in this space – that Mobility from Poverty is in reality comprised of three distinct fields:

- Economic Security

Stakeholders in this field focus on advancing day-to-day economic stability and securing the basic needs that individuals and communities require, before they can realistically project forwards towards their future aspirations. Their central belief is that agency is severely impeded if those experiencing poverty are persistently struggling to access essential services such as housing, healthcare, family support services, and adequate safety nets – including elements such as a living wage for all workers. Many stakeholders in this space will recognize that their work advances economic mobility by extension, but their focus is present-oriented rather than future-oriented, namely: eliminating chronic poverty.

- Economic Opportunity

Stakeholders in this field seek to facilitate Mobility from Poverty by focusing on providing a pathway up the income or wealth ladder, which individuals and communities can theoretically opt into and pursue over time. Stakeholders often focus on issue areas such as education and skill-building, work and income-building, and gaining access to equitable financial services that allow for the realization of personal goals (e.g. home ownership, establishing a small business, building credit-worthiness). While stakeholders in this space can, and do, also serve people experiencing severe poverty, they generally do so by equipping individuals to succeed over time rather than by catering to their most immediate needs.

- Economic Paradigms & Belonging

Stakeholders in this field direct their attention to defining and creating economic models and practices that foster greater justice or social inclusion. This may range from efforts to develop a form of capitalism that is better able to meet the challenges of the 21st century, to replacing capitalism altogether (at one end of the spectrum) or pushing for ever-freer markets (at the other end of the spectrum). Recurring concerns for many in this field are justice, inclusion, and belonging, i.e. which practices and principles will advance dignity for all, and afford appropriate power to priority stakeholders? While ideology shapes the work of stakeholders across all three fields, the field of Economic Paradigms & Belonging is often an area of intense debate on fundamental matters of principle, equity, and ethics in relation to the economic system.

The 12 issue areas cited further above frequently impact all three of the fields of Mobility from Poverty, they may also be grouped under the field they most impact for ease of reference, per the framework below:

In passing, we note that the focus of these three fields loosely reflects the spirit of prior findings by the US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty. In consulting with communities nationwide, the Partnership had noted that three pre-requisites to successful mobility from poverty were:

(1) Power & Autonomy (which is directly advanced by ensuring Economic Security)

(2) Economic Success (which depends on issues captured within Economic Opportunity)

(3) Being valued in community / society (part of the Economic Paradigms & Belonging field).

Making sense of these three fields requires enquiry across 6 dimensions

There are multiple ways to evaluate the maturity and current needs of a field that is under development. In this engagement, Camber opted to iterate on a pre-existing evaluation approach with the benefit of our own prior experience of effective field evaluation and feedback from field stakeholders on how best to calibrate the evaluation framework to the specificities of the Mobility from Poverty space.

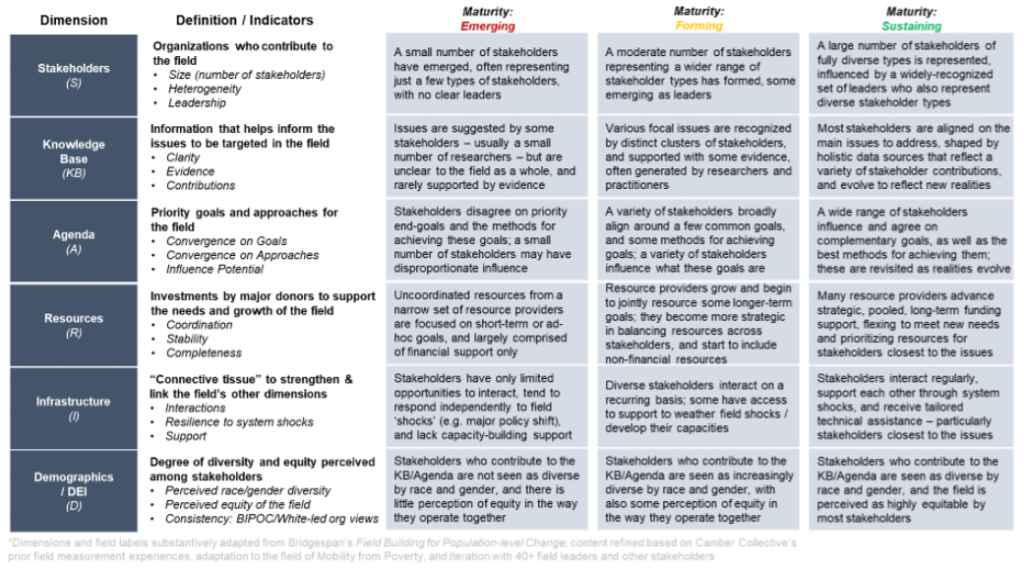

Specifically, we elected to assess each field according to the maturity level of its:

- Stakeholders

This refers to the organizations who contribute to the field. We focused on the size (number) of stakeholders engaged; the heterogeneity of those stakeholders by stakeholder type (i.e. ensuring there is a good balance of financial contributors such as foundations, directional contributors such as researchers or policy/lawmakers, and operational contributors such as frontline service providers); and the extent to which the field benefits from clear field leaders / field builders.

- Knowledge Base

This refers to the landscape of information that allows stakeholders to identify the issues that could be addressed by the field. Within this dimension, we evaluated the clarity of the knowledge base (i.e. how similarly is it recognized by different types of stakeholder); how deeply the knowledge base has been evidenced by data; and whether all stakeholders are able to contribute to it.

- Agenda

This refers to the field’s priority goals and agreed means of achieving those goals. Here, we studied the degree of convergence on goals and on the methods to realize them, as well as the degree to which stakeholders feel able to influence the goals or methods elevated by the field at large.

- Resources

This refers to the investments (of different types) of major donors to support the field. On this, we investigated the degree of coordination among donors investing in the field; the stability of those investments over multiple years; and how far that investment is complete (i.e. did it address a range of stakeholder needs).

- Infrastructure

This refers to various types of connective tissue, or supporting structures, that cut across the other field dimensions and enable it to function effectively at a practical level. We concentrated our analyses on understanding how far stakeholders have opportunities to interact with one another; whether there are mechanisms in place that allow them to be resilient to shocks such as unforeseen crises; and the degree of additional support made available to stakeholders beyond mere funding.

- Demographics

This refers to the level of diversity and equity perceived by and among stakeholders, along specific demographic lines. An initial analysis was conducted within the scope of this work, with deepened analysis to follow. We assessed the perceived level of racial and gender diversity within a field; the perceived degree of equity of the field; and the extent of variation in field perspectives according to the racial and gender identities of respondents.

Based on the data obtained from our field survey, field interviews, and independent analysis of external data points, the maturity level of each of these dimensions was then ranked asEmerging (i.e. initial stage of maturity), Forming (i.e. intermediate stage), or Sustaining (i.e. advanced stage). These maturity levels were then aggregated into an overall maturity level for the field in question (i.e. if a majority of dimensions were ranked at the Forming level, then the field overall was determined to be at the Forming stage).

Our approach is summarized in the visual framework below, which includes indicative descriptions of the different potential maturity levels for each dimension of a field:

We invite you to continue to our follow-on article for an overview of how the three fields currently compare as of 2021, and would welcome to discuss how your organization might help to advance the Mobility from Poverry space through each of these fields.

Other articles in this series:

Which Measure Of Economic Mobility Is Right For Your Organization?

Why is Interest in Economic Mobility Growing in the U.S.?